On Friday, November 11, we had a fascinating session by Dr MR Madhavan, co-founder and president of PRS Legislative Research.

The full recording of the session is available at:

About Dr MR Madhavan

Dr M.R. Madhavan set up PRS Legislative Research in 2005. His work is focussed on two related areas: strengthening the effectiveness of India’s Parliament and legislative assemblies by providing legislators with relevant research and enabling greater citizen participation in the legislative process.

Prior to PRS, Dr Madhavan worked for a decade in financial markets research at ICICI Securities in Mumbai and Bank of America in Mumbai and Singapore. He holds a B.Tech from IIT Madras, and MBA and PhD from IIM Calcutta, and has been honoured as a Distinguished Alumnus by both the Institutes. He was selected as the Business Standard Social Entrepreneur of the Year 2019.

Major achievements

India became independent in 1947 and the first Parliament was convened in 1952. Most of us have been born after 1947. So, we tend to underestimate our achievements.

At the time of independence, many pundits considered India to be a geographical space rather than one country. In Europe, nation states were characterised by one language, one religion and one ethnicity. India, on the other hand, was a land of multiple religions, languages, ethnicities, castes, etc. The consensus was that India would break up.

Experts also pointed out there was a strong correlation between per capita income and democracy. It looked unlikely that in a poor country like India, democracy would survive.

But India has surprised everyone. Except for one brief period during the emergency imposed by Mrs Indira Gandhi in 1975, democracy has flourished in the country.

Only 7 colonies which gained independence after 1945 became democracies. India was one of them. The remaining 6 are much smaller: Mauritius, Belize, Jamaica, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, with a population of less than 1 crore.

In short, staying together as a country and thriving as a democracy have been two major achievements of post-independence India. Indeed, we could argue it is democracy that has kept us together.

Parliament

Parliament (along with our state legislatures and local executive bodies) lies at the core of our democracy. Parliament has three functions:

Making laws: All the laws of the land are passed by Parliament.

Holding the government accountable: This is done through the various standing committees, discussions during question hour, no confidence motions, etc.

Overseeing the finances of the country: Any proposal to raise revenue through taxes must be passed by Parliament. Similarly, all government expenditures must be approved by Parliament.

In short, parliament gives legitimacy to the actions of the government. The ruling party has legitimacy because we the people have voted them to power. If we are not happy, we can vote them out in the next election.

Parliament also facilitates social (dowry, gender, caste), political (For example, the linguistic reorganization of states, 1956 though Mr Nehru had major concerns when the idea was first proposed.) and economic reforms (The government created an important role for the public sector after independence and more recently has started to emphasise privatization).

Major Concern

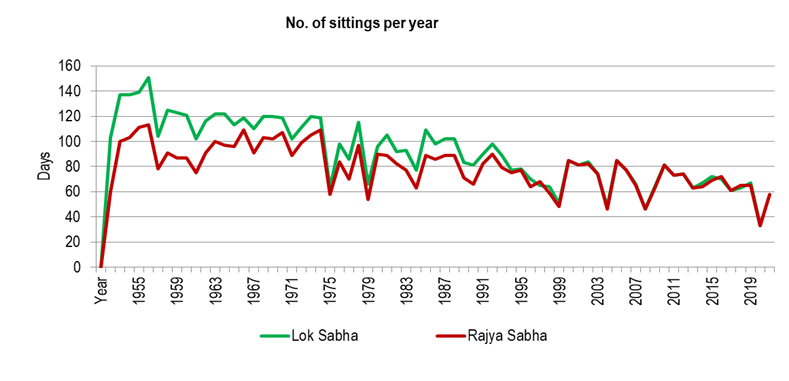

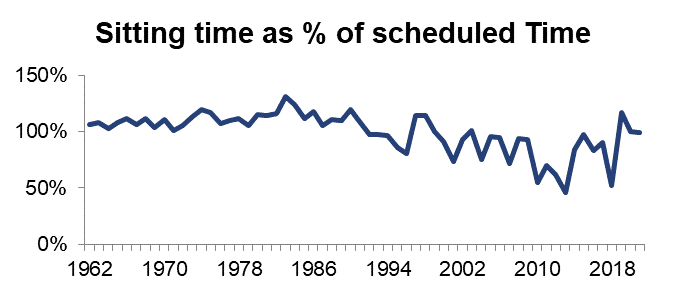

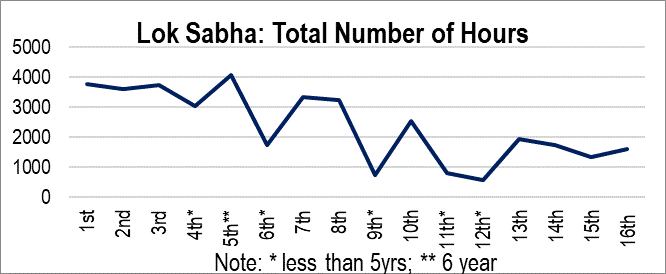

One major concern is that the sittings of Parliament have decreased from 120 days per year in the 1950s to 100 in the 1960s and 1970s and now less than 80 days. And even during the sittings, a lot of time is wasted due to disruptions. So many bills are passed without even a discussion for one hour. This was particularly so in the 15th Lok Sabha (2009-14).

Fewer bills are being referred to the Parliamentary standing committees these days. The number of trust votes and adjournment motions has decreased.

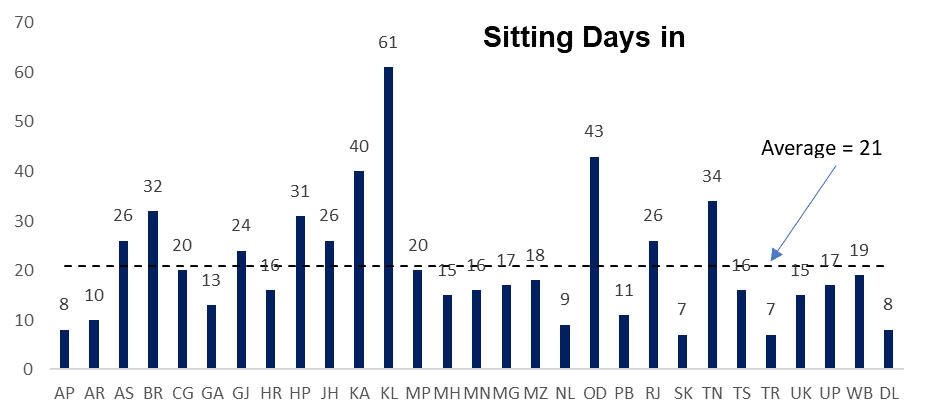

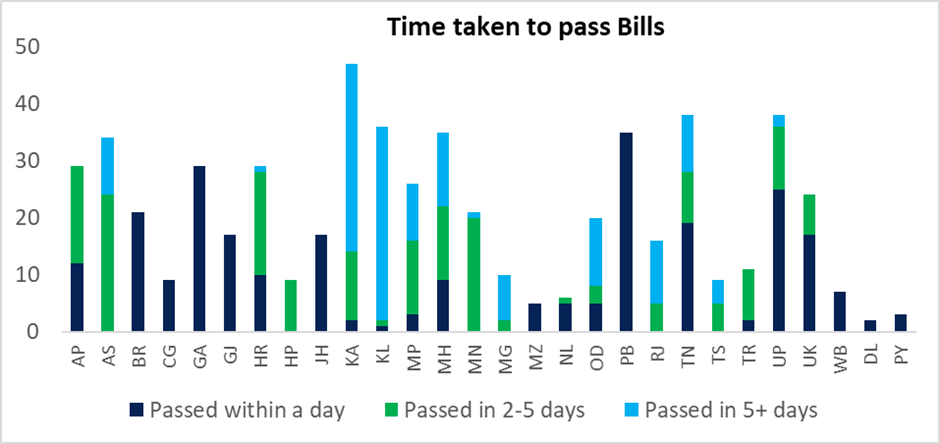

State legislatures are even worse. Delhi met only for 8 days and Nagaland for 9 days. Bills are often passed on the same day or the next day in states like Chhattisgarh and Goa.

The need for effective functioning of Parliament

Three reforms are the need of the hour:

Anti-defection law: This should be repealed. It goes against the basic structure of parliamentary democracy. Dr Madhavan explained this point in more detail during the Q&A. MPs represent their constituency and not their party. They should not vote, based on the party whip but on the basis of their conscience and the interests of their constituency. So putting restrictions on change of party is not logical.

Accountability: We do not know which way the MPs vote. Most voting happens through voice votes.

Providing tools to the parliamentarians to be more effective in their job. Currently, they do not get any research support. PRS was set up to fill this gap.

Q&A

On his journey

After graduation, Dr Madhavan worked for a decade in financial markets research at ICICI Securities in Mumbai and Bank of America in Mumbai and Singapore till 2005. His flatmate, Madhukar had worked with Pratham and then the Azim Premji Foundation. In his interactions with the government, Madhukar came to know that Indian parliamentarians did not have research support.

Dr Madhavan had developed good skills over a decade, in writing various kinds of research reports for banks. He wondered why he could not use these skills to do research for parliamentarians. That is how he returned from Singapore and his friend from the US, to set up PRS, largely with hope and no certainty that it would work. Within 2 years, they received a good response from MPs.

A well thought out law is a public good. So the founders felt that every MP should have access to good research, not only those with the money to pay. Such research should not be funded by the government as it may come with strings attached. PRS is largely run with donations and grants from Indian philanthropists. It has not been an easy journey. There have been cash flow problems but salaries to employees have always been paid on time.

On the evolution of the Indian parliament

Dr Madhavan drew an interesting comparison with the UK Parliament, the oldest in the world.

In the UK, parliament has evolved slowly over 800 years. The starting point was Magna Carta (1215) when a few feudal lords came up with the idea of curtailing the powers of the king and his government. Magna Carta challenged the concept that the King was divine and could not be questioned. Later, the rights of merchants were recognized. It took centuries for power to be transferred from the sovereign to the parliament. Today, the UK Parliament is supreme. In India, the Constitution is supreme. Parliament is subservient to the constitution.

India also has less MPs per unit of population (There are 550 Lok Sabha members for a population of 1400 million compared to 650 in the UK House of Commons. The UK has a population of only 68 million. The practical consideration here is that it would not be possible to accommodate more people in a room!) If we want to be more responsive to the needs of constituencies, we must reduce the powers of Parliament and give more powers to the state legislatures and become more federal. Currently, there is excessive centralization.

In the US, which has a presidential form of government, there is an emphasis on separation of powers between the executive and the judiciary.

We must remember that in many of the western countries, the constitution was framed by mostly whites (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, etc.). India is very different with a huge population and tremendous diversity. A well-functioning Parliament is needed to accommodate the fault lines and hold the country together.

On parliamentary mechanisms for listening to people

There are two formal mechanisms, Parliament has for listening to people:

Proceedings of the house: This is restricted. We cannot walk into parliament easily.

Standing committees of Parliament: Standing committees are of three kinds: Financial standing committees, Department related standing committees, and Other standing committees (OSC). These are more important and accessible to us if we have a point of view to convey. They have three roles to play:

- Bills are referred to them.

- They pick up subjects for examination.

- They look at the expenditure demands of the ministry.

These committees solicit views from the public and may even invite experts for a meeting. Dr Madhavan has appeared in front of standing committees at least 25 times. The members of the committee do not act as party members. If we have a credible point of view, the committee members are usually prepared to listen to us.

We can always approach MPs to convey our opinion. But when engaging with them, we must keep our reports short and to the point. Dr Madhavan provides crisp 5, 15 and 30 min reads for bills.

PRS does not have any advocacy agenda. It is more focused on keeping the MPs well informed especially about the key issues. For example, in case of the Telecom bill, PRS pointed out that the bill covers both wire and content. They are fundamentally different. Should they be regulated in the same way?

In the case of the Child marriage bill, there was a proposal to raise the minimum age of marriage for girls to 21 from 18 to bring them on par with men. PRS asked whether the marriage age of boys should be reduced to 18? At the age of 18, people enjoy the right to vote. So why not allow them to marry as well?

On improving stakeholder participation in the legislative process

The two reasons for lack of engagement are lack of intent and lack of awareness.

If people do not have the intent, ie are unwilling to engage, there is little we can do.

But we can do a lot to spread awareness. We can publicize the work of the standing committees. (PRS creates awareness on the social media of parliamentary committee related advertisements which appear in the parliament bulletin or on the tender pages of newspapers and are largely not read by the public).

We can collaborate with industry associations, unions and NGOs. We must question our own MPs on various issues. We are in general not good at this.

On the standing committees of parliament

The 31 members of the committee discuss what issues to focus on. They typically take up 10 subjects per year. We should try to approach and convince them. How do the committees get their inputs? Unlike in the US (The Congressional research service has 700 people, a $ 110 mn budget and is a part of the Library of Congress) and the UK (research cell), the research support to our parliamentarians is minimal. We may have a swank new parliamentary building, but the soft infrastructure is still lagging behind. It is like a majestic university building without any competent faculty.

On the need for a two-party system

The term two party system is a misnomer. In fact, no country, including the US, has a two-party system. What we call parties are largely coalitions of interests. Japan, Germany and Israel have many parties. What matters is not the number of parties but the legitimacy of the elections and our ability to hold the legislators accountable.

On holding state and parliamentary elections simultaneously

This can reduce expenditure significantly. But structurally, it is difficult. Yes. This used to happen in the years following independence. But it was relatively easy then. The Congress was the only party that mattered and came to power and formed stable governments at the centre and in the states, with rare exceptions like Kerala.

Today, the scenario is different. Governments can fall and midterm elections may be needed. For example, consider the Delhi state election of 2013. No single party could form the government but was willing to pull down any government that was formed. The only way out was to hold fresh elections.

So, it is difficult to hold state and parliamentary elections simultaneously. Even if we enforce simultaneous state and parliamentary elections to begin with, over time, because of similar incidents, there is likely to be a phase lag.

Of course, to increase continuity and reduce the possibility of midterm elections, we could think of using the German system, where parties can vote out a government only if a new government can be formed. Otherwise, the existing government continues. But this would lead to a loss of legitimacy for the government.

On improving the voter turnout

Turnout is better in the rural areas as voters are more involved and pay more attention to who represents them. In the urban areas, turnout is less as voters may be less bothered. In fact, in rich countries, the voting share is lower. We could make voting compulsory like Singapore and Australia, with heavy fines imposed for not voting. But that goes against the concept of freedom.

On the anti-defection law

The argument is that we vote for parties and not individuals. Without such a law, MPs may switch parties under the influence of money or power or threat.

Dr Madhavan argued that the term political party did not find any mention in the constitution till 1985, when the anti-defection law was introduced.

We vote for a person and not for a party. The person is accountable to the constituency and not the party. The MPs should be able to question the government when the situation demands.

The anti-defection law seeks to provide a stable government by ensuring the legislators do not switch sides. However, this law also prevents a legislator from voting in line with his conscience, judgement, and interests of his electorate. Such a situation impedes the oversight function of the legislature over the government. Members vote based on the decisions taken by the party leadership, and not what their constituents would like them to vote for.

Dr Ambedkar had argued in a speech at the Constituent Assembly on Nov 4, 1948, that compared to the presidential form of government, the parliamentary form of government ensures more accountability though at the cost of stability. In a country like India, accountability is more important.

The anti-defection law puts pressure on MPs to toe the line of their parties. It does not prevent defection. It only encourages legislators to change their party enmasse. We have only moved from a retail sale of MPs and MLAs to a block sale! Only a handful of countries like Pakistan, Zimbabwe, Guyana, Bangladesh and Sierra Leone have a similar law.

Why should we be worried about politicians changing their party? They are accountable to the constituency. They must vote on an issue depending on how they feel it will benefit the constituency. The party they belong to, should not matter.

The real solution to the problem is clear ideology. If parties define their ideological positions clearly on most key points, there will be less defections. Except for the CPM and BJP, other parties do not have a clear ideology.

The right way for people to punish MPs who act wrongly, is to vote them out during the next election. When Jyotiraditya Scindia defected along with 24 MLAs from the Congress to the BJP, most of them were reelected.

On increasing parliament time

There is an inherent contradiction. Parliament’s job is to hold the government accountable for its actions. The parliament is summoned by the President on the advice of the government. So where is the incentive to have longer sittings of Parliament?

We should bring more public pressure and ensure media coverage. We could also publish an annual calendar like in the UK and not leave it to chance for Parliament sittings to happen. There should also be a provision that if the opposition party members want a session, then Parliament should be summoned.

On the use of AI

Certain activities can be automated using machine intelligence but where judgment is involved as in key negotiations involving different stakeholders, there is limited scope for the use of AI.

On social media and their influence on voting

The issue came to the forefront during the 2o16 US Presidential elections. But it has probably been hyped up more than it should have. Facebook may have targeted people with highly personalized messages. But it was up to the individual voters whether to be influenced or not. The voting was not rigged. Attempts to influence voters are not new. Earlier, we used media such as television to do this. While social media is heavily criticized it provides a more level playing field compared to mass media such as television. Television ads and election rallies, which also aim at influencing voters, require money power.

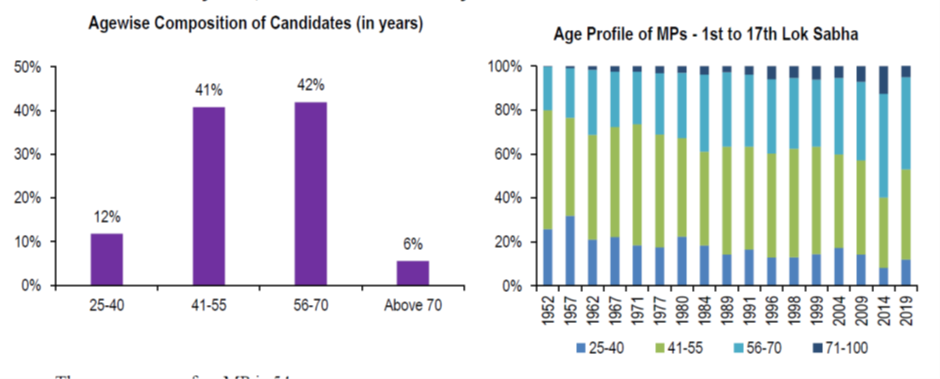

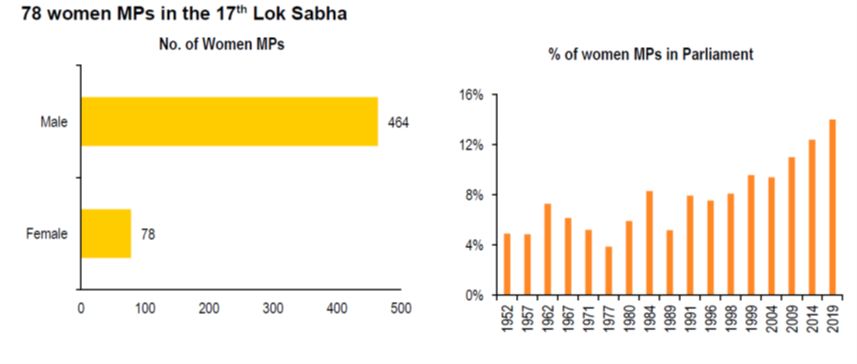

On the need for greater representation of young people and women

The parliament is dominated by older, male politicians. Women (their share has increased gradually from 5% in 1950 to about 14% today) and the youth are underrepresented in parliament. The solution may not lie in reservations (as the reserved category may be perceived to have an unfair advantage) but in voting out older male politicians and electing younger politicians and women. Unfortunately, we do not use our power as voters very effectively.