An evening with Mr. Tamal Bandyopadhyay

Introduction

On Thursday, Nov 21, we had the 172nd session of WiseViews Leadership Conversations series. The speaker was Mr. Tamal Bandyopadhyay, an award-winning author and renowned columnist. Mr Bandyopadhyay is currently Consulting Editor of Business Standard and a Senior Adviser to Jana Small Finance Bank Ltd. The topic was: Financial nclusion through small finance banks.

About Mr Tamal Bandyopadhyay

Mr. Tamal Bandyopadhyay has dedicated nearly three decades to the study of the Indian banking sector. He has played a pivotal role in shaping financial discourse in India. His weekly column, “Banker’s Trust,” published in Business Standard, is celebrated for its incisive analysis and informed opinion that resonate with both industry professionals and the general public.

Mr. Bandyopadhyay is the author of several bestselling nonfiction works. His critically acclaimed book, “Pandemonium: The Great Indian Banking Tragedy.” has received multiple prestigious awards, including the Tata Literature Live Best Business Book Award and the KLF Best Business Book Award. His other notable books are “Roller Coaster: An Affair with Banking,” “HDFC Bank 2.0: From Dawn to Digital,” and “Sahara: The Untold Story.” Based on the last book, an OTT is being made by noted director Hansal Mehta for SonyLIV.

Mr. Bandyopadhyay was nominated by LinkedIn as one of the most influential voices in India for three consecutive years and was listed among the top 10 writers in finance worldwide. He received the Ramnath Goenka Award for Excellence in Journalism in 2017.

Mr. Bandyopadhyay played a key role in establishing the financial daily Mint. He also served as an adviser to Bandhan Bank Ltd, the first Indian microfinance company to transition into a universal bank.

Understanding Financial Inclusion

Financial inclusion is not just about access. It is also about affordability. Financial inclusion spans various financial products including savings, credit, payments and insurance. The term was first coined by Dr YV Reddy, the RBI governor during the April 2005 monetary policy. Dr D Subba Rao carried the concept forward. Dr Raghuram Rajan contributed by helping set up small finance banks.

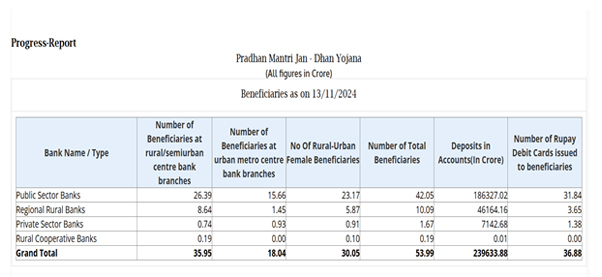

Financial inclusion got a major fillip with the Jan Dhan Yogana. Till date about 54 crore savings accounts have been created with an average deposit of Rs 4000 per person. Of the total number, more than 42 crores have been created by the public sector banks with the private sector accounting for only 1.67 crores. (See table above.)

Banking in India

Modern banking in India originated in the mid of 18th century. The largest and the oldest bank which is still in existence is the State Bank of India (SBI). It originated and started working as the Bank of Calcutta in mid-June 1806. The period between 1906 and 1911 saw the establishment of many banks inspired by the Swadeshi movement.

By the 1960s, the Indian banking industry had become an important tool to facilitate the development of the Indian economy. At the same time, it had emerged as a large employer. The Indira Gandhi government with its strong socialist leanings felt it was time to nationalize them. Bank nationalisation was carried out in two phases.

| First Wave of Nationalization (1969) | |

| Allahabad Bank (now part of Indian Bank) | Indian Bank |

| Bank of Baroda | Indian Overseas Bank |

| Bank of India | Punjab National Bank |

| Bank of Maharashtra | Syndicate Bank (now part of Canara Bank) |

| Central Bank of India | UCO Bank |

| Canara Bank | Union Bank of India |

| Dena Bank (now part of Bank of Baroda) | United Bank of India (now part of Punjab National Bank) |

| Second Wave of Nationalization (1980) | |

| Oriental Commerce Bank (now part of Punjab National Bank) | Andhra Bank (now part of Union Bank of India) |

| Corporation Bank (now part of Union Bank of India) | New Bank of India (now part of Punjab National Bank) |

| Vijaya Bank (now part of Bank of Baroda) | Punjab and Sind Bank |

Private sector banks

Following the liberalisation of 1991, the launch of private sector banks became a reality. Among the private sector banks which came into existence in the first round were UTI Bank (rechristened Axis Bank), IDBI Bank, HDFC Bank and ICICI Bank -- all of which had the backing of strong financial institutions. Others were Times Bank (which merged with HDFC Bank in 1996), Indus Ind Bank, Centurion Bank (which first merged with Bank of Punjab and finally with HDFC Bank) and Global Trust Bank (which failed and was merged with Oriental Bank of Commerce).

In 2002-03, two more private sector banks were created: Kotak Mahindra Bank and Yes Bank. In 2015-16, IDFC Bank and Bandhan Bank launched their operations.

| List of New Generation Private Sector Banks Set Up in the First Round | |

| HDFC Bank | Centurion Bank (merged with Bank of Punjab and then HDFC Bank) |

| ICICI Bank | Global Trust Bank (merged with Oriental Bank of Commerce) |

| IDBI Bank | Times Bank (merged with HDFC Bank) |

| UTI Bank (Now Axis Bank) | IndusInd Bank |

Thus, in the last 20 years, the doors have been opened to the private sector banks three times.

| Other New Generation Private Sector Banks Set Up Later |

| Kotak Mahindra Bank |

| Yes Bank |

| IDFC Bank |

| Bandhan Bank |

Small Finance Banks

The Nachiket Mor Committee was formed in 2013 to study financial inclusion in India during the tenure of RBI governor, Raghuram Rajan. The committee (final report submitted to the RBI on January 7, 2014) recommended issuing specialized bank licences to focus on narrow areas of specialization. These included payments banks.

But payment banks did not take off well as their business model is not exactly viable. Only the telecom companies are in this space to take care of customer needs and increase customer loyalty. Before these, in the late 1990s, Local Area Banks were also set up. They too did not click.

Small Finance banks

In July 2014, the RBI released the draft guidelines for small finance banks. The final guidelines were released in November 2014. In February 2015, RBI released the list of 72 applicants. In September 2015, the RBI gave provisional licensces to ten entities, eight of which were microfinance NBFCs. Capital Local Area Bank was the first small finance bank to begin operations, opening with 47 branches on 24 April 2016.

| List of Small Finance Banks Approved in 2015 | |

| Capital Local Area Bank Ltd | ESAF Microfinance |

| Ujjivan Financial Services Pvt Ltd | RGVN North East Microfinance Ltd |

| Janalakshmi Financial Services Pvt Ltd | Suryoday Microfinance Pvt Ltd |

| Equitas Holdings Pvt Ltd | Utkarsh Microfinance Pvt Ltd |

| Au Financiers India Ltd | Centrum Financial Services Limited |

In April 2021, Uttar Pradesh based Shivalik Mercantile Co-operative Bank became India’s first urban co-operative bank (UCB) to transition to a Small Finance Bank (SFB). Since these banks began operations, only one bank’s management has changed: RGVN.

Business Model

Small finance banks (SFB) provide basic banking services: deposits and lending. They have been created to cover sections of the economy not being served by other banks, such as small business units, small and marginal farmers, micro and small industries and unorganised sector entities. These banks must open at least 25% of their branches in unbanked regions. 75% of the net credit should be for the priority sector, and 50% of the loans must be less than ₹25 lakh.

The minimum paid-up equity capital for small finance banks is ₹200 crore. In view of the inherent risk, these banks must maintain a minimum capital adequacy ratio of 15 %. Tier I capital should be at least 7.5 % of RWAs (risk weighted assets). Tier II capital cannot exceed Tier I capital.

For these banks, small finance appears to be an intermediate milestone and not a destination. Most of them aspire to become universal banks and not just serve the underprivileged and priority sectors. AU Small Finance bank has already submitted its application to the RBI in this regard.

The small finance banks are struggling to raise deposits. Since they are referred to as “Small” Finance Banks, there is a trust deficit. Why would depositors keept their money with them? Moreover, the underprivileged segments they are meant to serve do not have adequate savings. So, they are compelled to mobilise deposits in the urban pockets. The only weapon they have to compete with the bigger banks is higher deposit rates. (Unity Small Finance Bbank offers 9.5% interest rate to senior citizens.)

There are effectively two banks within each small finance bank: one to raise deposits in cities and the other to lend money in the hinterlands. Maintaining a presence in the cities requires heavy investment. The cost of compliance is also high.

In general, since the small finance banks began their operations, the business environment has not been favourable. They have been impacted by GST, demonetisation and Covid. For secured loans, they compete with apps and other entities which push loans, aggressively charging high interest rates. The balance sheets of the small finance banks are stretched. So, they are moving into secured loans to cut credit losses.

Concluding remarks

In short, small finance banks are moving away from their original charter. No longer is financial inclusion their paramount goal. All of them except RGVN are listed entities. They are under pressure to meet shareholder expectations. They l aspire to become universal banks.

It is true that the country has made a lot of progress in financial inclusion in the last 20 years. The RBI should be given due credit for this. But the small finance banks have not contributed much in this regard. However, they have their utility, and the banking ecosystem does need them.

Q&A

Statistically, we have made a lot of progress. The large number of Jan Dhan accounts is a good example. But the ground reality is not presenting an encouraging picture. Poor people still find it difficult to get loans from the formal banking sector.

Think of our drivers or maid servants. They aspire for a better life for their children. For this they need loans. But banks do not find them creditworthy despite having KYC documents. So, it is left to their benevolent employers to act as the bank.

Even if financial inclusion has improved, affordability is a major concern. The “new generation of moneylenders” is exploiting customers and charging very high interest rates. Technology can be a big enabler, but it can also be misused. Many of the players are unregulated entities. Access, affordability and responsibility are the need of the hour. We have a long way to go in this regard.

There are some good examples of how financial inclusion has increased in recent years. Gold loans have become popular in recent years. Earlier, people were reluctant to pledge their gold. Lenders also found it cumbersome as many borrowers would return the money earlier and reclaim their gold. Now in addition to traditional players like Muthoot Finance, many banks provide gold loans. Monetisation of gold is happening. Affordable housing is another example. With the increasing formalization of the economy and the availability of GST and other data, supply chain financing is also taking off. Banks are also learning the nuances of cash flow-based lending.

In Bangladesh, microfinance institutions (MFIs) can raise deposits. In India, they cannot. The RBI is uncomfortable with these institutions mobilising public deposits. There have been many Ponzi schemes operated by the NBFCs and spectacular instances of entities going bust. Millions of depositors have been defrauded. So, the RBI is cautious in its approach.

Following the Andhra Pradesh crisis of 2010, the MFIs got into trouble. The crisis was caused by several factors. The MFIs pursued growth at all costs, ignoring warnings and building their business model on shaky foundations. The MFIs charged high interest rates and used unethical practices to recover loans. Many borrowers committed suicide due to these coercive practices.

In the aftermath of the Andhra crisis, the RBI set up a committee headed by noted chartered accountant YH Malegam to look at the sector and frame guidelines. In sych with the Malegam Committee’s recommendations, the margin (spread) for large MFIs was capped at 10%. So, if the borrowing rate was 12%, the lending rate could not exceed 22%. This was one of the many changes that the sector had to face.

In 2022, the RBI freed up the interest rates. Following that, many lenders raised their lending rates. If prepayment fees, late payment charges, processing fees (and add-on sales of consumer products) are all considered, the interest rate is effectively 40-50% for some of the NBFC-MFIs. So, MFIs are the modern day money lenders for all practical purposes. They have not used the freedom to set interest rates responsibly. The RBI is upset with this.

In short, private lenders are exploiting borrowers with opaque practices. The burden of financial inclusion as mentioned earlier still rests heavily with the public sector banks.

It is expensive for banks to reach these vendors on their own. Technology can reduce costs and improve reach. Banks can leverage banking correspondents on the ground to originate loans and enable recovery. The way forward is collaboration and not competition. Banks must work with the different entities and see how to complement each other.

Some Jan Dhan bank accounts have been hijacked by fraudsters and used for illegal purposes. The actual account holders may not be aware that their accounts are being used in this way. Particularly after the 2016 demonetization, large amounts were deposited in otherwise dormant Jan Dhan accounts. This is a classic example of how technology can be misused to server ulterior motives.The RBI has constituted a committee to look into the matter. By and large, these accounts are KYC compliant. So weeding them out is difficult.