An evening with Mr Dhirendra Pratap Singh

Introduction

On Friday, May 30, we had an insightful session by Mr Dhirendra Pratap Singh, co-founder and CEO of Milaan Foundation. It was the 196th session in the Wise Views Leadership Conversations series. Mr Singh shared insights on gender equity and women education in rural India. He discussed the challenges faced by adolescent girls, the importance of long-term investment in gender equity, and Milaan Foundation's approach to measuring and organizing social impact. He also covered the implementation of girl empowerment models, financial sustainability, and potential collaboration opportunities with educational institutions to raise awareness and support girls in rural India.

The recording of the session is available by clicking the link below.

Watch the recording

About Mr Dhirendra Pratap Singh

Mr Dhirendra Pratap Singh is the Co-Founder and CEO of Milaan Foundation, a non-profit working towards educating, enabling and empowering children and youth in rural communities. He also co-founded the impact venture Azadi Inc. in 2012, to create 'Menstruation-Friendly Schools' under Milaan in rural Uttar Pradesh, India.

Previously, Mr Singh had several successful forays developing strategy and scaling up operations for organizations within the development sector. This included acting as the Managing Trustee of Vidya Grants India, a subsidiary of Vidya Grants Foundation, USA. During his time at Vidya Grants India, Mr Singh launched and scaled their operations in India.

Mr Singh has earned a Masters in Development Studies from Amity University and earned a Bachelors in Mathematics (Hons) from University of Delhi. Various national and international organizations such as Oxfam International, Pravah, Ashoka, Action for India, HundrED.org and the International Peace Foundation have recognized his work and honoured him with awards and/or fellowships.

On the importance of gender equity

Gender equity is not a charity or CSR issue. It is a growth issue with an economic imperative. It is a leadership issue. It is everybody’s fight.

Mr Singh began with the story of Roshni, a poor girl from Sitapur. Thanks to the support of Milaan, Roshni is now a confident young girl and ready to go to college. Like Roshni, Milaan has many other success stories.

India is home to about 120 million adolescent girls. That is almost one third of the size of the population of the US. Most of them live in rural India and suffer from systematic exclusion.

These adolescent girls end up performing about 5 to 7 times more domestic labour than boys. They drop out of the school earlier. Their access to healthcare is limited. Almost 40% of them don't complete secondary education. One in 4 get married before the legal age of 18, making India the home to the largest number of child brides in the world.

According to the World Bank, if every girl in the world clears Class 12, it will add about $ 30 trillion to the global economy. This is almost the economy of the US and 7.5 times India’s GDP of about $ 4 trillion. Just ending things like child marriage may add about $ 500 billion annually to the world economy. Life expectancy will go up. A child born to a mother who can read is 50% more likely to survive beyond the age of 5. There’s a higher probability that educated women will educate their children. Every additional year of secondary education can increase the life expectancy of women by 15-25%. It will change the entire dynamic of the world we live in.

Elusive SDG 5 goal

SDG 5 talks about gender equality. But a recent report, by a group called Equal Measure, mentions that not even a single country on the planet is on track to meet the gender equality goal by 2030. Why is this not happening? One of the main reasons is that we are not investing enough time and effort in this space. The Women Philanthropic Institute says that less than 2% of the global donations goes to courses for women. This is a pity. They constitute about 50% of our population with high potential.

We know what could happen when we solve the problem. Then why are we not solving the problem quickly? This is not a problem that needs a new technology or a heavy level of financing. It is all about prioritization and paying attention.

The story of Milaan

Milaan started its operations in 2007. The government had invested in schools. But the presence of a school did not guarantee that girls attended school. There were gender barriers. Milaan stepped in and has made a tremendous impact in the last 18 years. It has built a network of over 5,000 girl leaders as role models in about 5,000 villages across 3 states in India.

Milaan identifies girls who have the potential to be girl leaders. It enables them to grow and develop, by putting them through a leadership program. These girls are then called girl icons. Every girl mobilizes about 20 more girls in her own community, forms a peer group and supports them with the information that they need. Then these girls come together towards the middle of the program to identify an issue and develop a solution. It could be a campaign around child marriage or around creating awareness around menstrual health, or how to get the washrooms in the school operational.

Milaan teaches the girls life skills and gives them access to technology and prepares them for careers. Milaan has learnt with experience that there is a need to work with the entire community, local government, local stakeholders and not just girls in isolation.

Milaan’s partners include the likes of Obama Foundation, the Ford Foundation, Global Giving, Belden, State Street, etc.

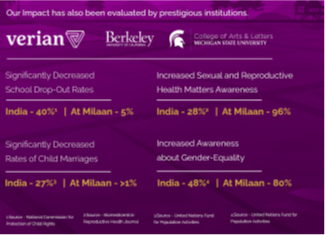

Milaan’s model has been evaluated by third parties, including UC Berkeley, Michigan State University, Verian. Milaan has been able to bring down school dropout rates from 40% to less than 5% and child marriage rates to less than 1%.

Milaan has an ambitious agenda. It is currently working on a strategy to work with over a million girls by 2030. This would involve a leap from covering 100,000 girls in almost 18 years to working with a million girls in the next 5 years.

Concluding remarks

There is wide acknowledgment today that the future is not just urban and digital. It is equitable growth.

Girls like Roshni do not want charity. They're looking for space to grow, to lead, to build, like most of us. But the difference is that when these girls do that, they uplift their entire community. Milaan sees these girls not just as beneficiaries of change but as the architects of India's future. So, the question is not what we can do for the girls. The question is, what might we become if we walk besides them.

Q&A

Mr Singh grew up in in a lower middle-class family. His grandparents were farmers. His dad got into the army to support the family. Like every other, middle-class family in this country, the focus was always on education. As he grew, his plan was very clear: do an undergrad from a good college and then an MBA. He did get into an MBA but then dropped out.

Mr Singh was and is still very excited about mathematics. It has taught him to look at the data behind the story and the story behind the data. When we are deciding where we want to invest and how we want to intervene, the data tells us a good story.

Milan started as an education organization, with a small learning center in Sitapur. But Mr Singh noticed that girl attendance was an issue. The data revealed that a lot of young girls were being left behind. And that's where Milaan’s intervention changed. (When we look at the data, the question to ask is, who are we leaving behind? We celebrate people who are progressing and that we should. But we should also be asking: Who are we leaving behind?)

When Mr Singh decided to set up an NGO, no one in his family had an idea of what it was. So, it took some time to get into this space. After he got into the space, Mr Singh realized the need to professionally upskill himself. He did his master’s in development studies and then a leadership program from IIM Bangalore. He has done multiple leadership programs, at various stages of his life to make sure he is growing and making a greater impact.

Milaan operates in a very challenging environment. The funding is limited. In the rural areas building a team is not easy. For most people, the aspiration is to move to the cities. People may be ready to work in rural areas as a hobby or an internship, or a small sabbatical. But they may not want to build their careers in rural India. At the same time, it is not easy to walk into a community and then suddenly say that child marriage is not a good thing to do. Changing the mindset of the villagers is indeed challenging.

But the good thing is that the return on investment is humongous. When Mr Singh sees the impact his work is having, he forgets all the challenges that he is facing. As he mentioned, in India, parents spend all their life and money to raise their children. And if those children do well in life, that's their greatest achievement. Here Milaan is working with thousands and thousands of them. Supporting and educating them changes the entire trajectory of the economy and society. That realization takes away all the pain.

Our mindsets get shaped by the ecosystem we grow in. Milaan recently asked some boys to do simple household work like brooming the veranda. The reactions from mothers were: You are a boy. Why would you pick up a broom? It is intergenerational, complex, but at the same time human created. So we can change the mindset. The mindset changes when we begin looking at the opportunity. How does it bring more aspiration, pleasure, equity within our relationships?

When Milaan started its operations way back in 2007, parents had to be convinced to send their girls to school. Then a time came when they knew they should send their daughters to school, but they would still not send them. And then the right to education came in 2021. People started sending their girls to the primary school. So it was a beginning.

Change takes time when it comes to societal structures. It is important to look at things from a community lens. We must also realize that it is the fathers and the mothers who ultimately have to say: “I will educate my daughter. I'm going to support her. She might be the first one to go to college, but she will go.” Mr Singh has seen fathers who spend one and a half hours each way for dropping their daughters at school and picking them up. And these are daily wage earners.

The theory of tipping points says, if we can convince 25 – 30% of a community, the mindset starts changing very, very quickly. Then there is the concept of movable middles. Some people are very rigid and some are very liberal. But there's a large population which sits on the middle. Those are the people who are easy to convince.

Many funders have short term goals. CSR projects often have a 1 year horizon. if we are lucky, we get 3 years to deliver results. We can’t expect to walk into a community and bring about change within 12 months. It doesn't happen with our own children. A lot of work is required. But there are some donors who are very patient and willing to spend a couple of years to understand how this works and see the impact.

Often after a donor meeting, people say: This is a women and girls cause. You should talk to my wife. So, it is often treated as an issue pertaining to women and girls. But it is everybody’s issue. it's also important to ensure that our investments, both financial and non-financial can include the most vulnerable girls from vulnerable communities.

When people get awards, they often thank their mother. The question we should be asking is: How do we invest in a space where that girl can become the mother of another successful person? That is how intergenerational change happens. It takes time to change that mindset.

We should work not just with our heart but also with our brain. If we work with 1,000 girls, we can always find a few girls like Roshni, who are doing well. And that's great. But what is that common minimum denominator.?

It is important to look at important milestones in the life cycle. If the data shows that there is a high probability of a girl dropping out after Grade 6 we should focus on bringing that dropout rate down.

The moment she drops out, the domestic labour increases, her learning stops, and in a couple of years, the parents start looking for a groom. So, she becomes a child bride at 16-17. If she has an early child, her health gets impacted, the child's health gets impacted, and the vicious circle continues. So, the first indicator is continuation and completion of secondary education.

For example, the average age of a girl completing Class 12 in India is about 17 years. If we ensure that we can get her to clear Class 12, she is academically stronger to pursue a career. Also, she is unlikely to be forced into a child marriage and become a teenage mother.

The second is around directly delaying child marriage. How do we do one to one mapping and track every girl in the program? How do we encourage conversations for delaying child marriage? A small conversation over a cup of tea can change things. Who in the family or community can lead this conversation? it could be the village Pradhan.

We must also build self-wellbeing and self-esteem within girls. Girls in rural India, have grown up feeling their job is to just take care of their husbands, their children, their brothers, and others in the family. They're not stepping back and thinking about what they really want? Health and self-worth are correlated. Girls should realize that they matter and there’s a constitution that protects them, too.

One of Mr Singh’s favourite scenes from the movie Lapata Ladies is where the mother-in-law says, “I really like this dish, but nobody else likes it. The men in the house don't like, so I don't cook it.” The daughter-in-law says, “why don't you cook it?” And the mother in law’s response is: “Oh, now will we make food as per women's choices?”

The key questions around health for adolescent girls are: How do I take care of myself? How do I take care of my menstruation? Where do I get sanitary pads from? How do I know how to manage it. How do I make my own choices? When do I have a sexual partner?

Mr Singh was part of a research project on domestic violence in Rajasthan during his masters. The look on the faces of the women conveyed: Why are you talking about it? I don't have a problem with it. Why do you have a problem with it? And that left Mr Singh wondering: How have we come to a stage where it is acceptable for somebody to be hit and think it is perfectly normal? So it is important to keep girls in schools and make them aware that there is a constitution to protect them.

Milaan’s approach has been to understand the major break in points in one's life and how to support women during those critical moments. Milaan has used data to measure the impact during those transition points.

India is one of the few countries globally that has a child marriage data set and a strong policy framework. The Child Marriage Act has been there for many years.

On the roads, if we jump the traffic light or don't wear a helmet, we must pay a fine. The enforcement is done by the traffic police. Government officials also go to schools and colleges and create more awareness around following traffic rules and wearing a helmet.

Now child marriage has been a part of our Indian culture. And we are trying to uproot it. There is a complexity because you can't just force it. A mindset change is needed.

We must identify the pockets which need interventions. Child marriage rates are high in very specific pockets in the country due to cultural, religious or economic factors. We need to precisely identify these pockets. Then we should figure out how we can intervene. We must understand the triggers. We should make sure more girls are in school, especially at the secondary level. Almost 97% of our girls are in primary school. But in secondary school, that number drops significantly.

Norm change and mindset change are very political in nature. So, for example, if we say there are more child marriages in a particular area, local community leaders might say they are being targeted. We may recall that the women's movement used to say, personal is political. Understanding who the leaders are and how it affects them is important.

Ironically, even the educated people are asking: if our girls get educated, will they get married? if they are outspoken, will they get married? Will they be able to adjust to the demands of their in laws?

People have remarked: Why are these girls sitting in a circle in a public space? Or why is she going to Lucknow to attend a training? Sometimes it's the parents. But most of the times it's the relatives, and it is the village head or the cast head. In general, people are scared and do not want to disturb the equilibrium.

With more and more girls doing well in the board exams, some people have started to feel that the boys are being left behind. And they are talking of a boy’s empowerment program!

To understand those vested interests is not easy. But when we are trying to bring about change, we must try to understand, who we are disturbing, who's going to get comfortable or who is going to get uncomfortable.

About 600 million girls live in the global South. We have seen many empowerment models coming from the US, Canada and Europe to countries like India, Bangladesh. But there are very few models that have moved within the south.

Milaan has tried to take its successful girl Icon program to Uganda. The NGO has done a pilot with approximately 1,000 girls in 2 districts in Uganda. Only 20% of the girls in Uganda go to secondary school. When we move to a new country the cultural context is very different. The vocabulary is very different. in India, we talk about girl icons building peer groups. But the peer group concept in Uganda has a negative connotation. The curriculum must change but the core of the model can remain the same. Milaan has a dream of working with a million plus girls in Uganda. Milaan might be looking at other countries over time as it figures out the funding scenarios.

Today, boys are getting more and more aspirational about having a more educated partner. They are also trying to understand what it means to have a wife who has a voice, her own opinions, and her own choices. That implies a major change. They have been used to seeing their mothers play a passive role as housewives.

The attitude towards allyship is changing because people are seeing the strength in it. They are seeing the value of both partners playing almost equal roles in the family from bringing money home, to taking care of children to taking care of households.

But it’s still a long journey to go and the stereotypes are well entrenched. Even in the cities, a man will always ask his wife to get a glass of water. He will not go and do that. In most of urban India, both the husband and wife work. When they come back from work, the wife enters the kitchen to make sure there's dinner. Even if there is house help, she's responsible for making sure the house is in order. The husband switches on the TV and watches news and enjoys dinner.

So, it's a different level of complexity when it comes to gender equity. To understand what it means to be an equal partner in a relationship is a question that a lot of young men are asking. And more sensitization is needed in this regard.

Under Section 80 G, 50% of the donation amount is exempt from income tax. Interestingly, in countries like the US, the tax exemption is almost 100%. But there are special projects for which the Government of India allows 100% tax exemption.

More than corporates, bulk of the financing should come through crowd funding, from the common people. The power of many people, each contributing a small amount, is formidable. For example, in Milaan's case, it costs about ₹3,500 to support a girl, to go through a leadership program over 18 months. That is not a big amount. And people can certainly chip in.

If we involve institutions, there will be vested interests, that dictate how the funds will be used, where they will be invested and so on. But people can make a larger difference. And Mr. Singh has seen many successful projects because of people's support.

Despite limited resources, Milaan has continued to grow rapidly thanks to the alumni. Indeed, they have been a major factor. Alumni give back not financially (they have just started their career.) but their own time. So almost 80% of the teams for the girl icon program is made up of the alumni from the program. And they sign up as mentors, guides, supporters and even trainers. The alumni combined with technology is how Milaan has been able to scale up almost 6 to 7 times in the last 3 to 4 years.

Milaan’s journey started from the school. There was no school within a 13 kilometre radius when Milaan began its operations. So, the community came together and asked: Can we build a school? Now of course, there are more schools. But the school remains the heart of what Milaan does. Milaan has learned and grown from there and built its network. Indeed, Milaan is proud of its origins in Sitapur, where it has built the school.

Educational institutions can build awareness among students of how we are leaving behind adolescent girls. Many students are not even aware of child marriage. When they graduate and go into a position of power, these students can do something about it and empower adolescent girls. The educational institutions can also provide financial support for some of the girls to come to college. The institutions can also partner with Milaan for providing students internships, projects, exposure trips.