An evening with Mr Ashish Kothari

Introduction

On Friday, Dec 27, 2024, we had an insightful session by Mr Ashish Kothari, Founder-member, Kalpavriksh and a leading social activist of India.

About Mr Ashish Kothari

Mr. Ashish Kothari has taught at the Indian Institute of Public Administration, coordinated India’s National Biodiversity Strategy & Action Plan, served on the boards of Greenpeace International & India, ICCA Consortium and been a judge on the International Tribunal on Rights of Nature. Mr. Kothari helps coordinate Vikalp Sangam (www.vikalpsangam.org), Global Tapestry of Alternatives (www.globaltapestryofalternatives.org), & Radical Ecological Democracy (www.radicalecologicaldemocracy.org). Mr Kothari is Co-author/co-editor, Churning the Earth, Alternative Futures, and Pluriverse: A Post-Development Dictionary

Multiple intersecting crises

We are facing multiple intersecting crises today:

- Ecological: biodiversity, climate, pollution

- Socio-economic: inequality, deprivation

- Political: conflicts, authoritarianism

- Cultural: colonisation and homogenization of knowledge, art, faiths, cuisines, languages

- Personal: depression, meaninglessness, alienation from roots/place/space.

Development

Development has produced economic benefits, but it has also involved violence against nature. Mr. Kothari showed an advertisement by a construction company proclaiming how its pipeline would rip through the jungles of Indonesia.

Due to such violence, the people who depend on nature for their livelihood have been severely disadvantaged. They include fishers, farmers, craftspersons and forest-dwellers. They make up about 65% of India’s population.

What we today pose as solutions are technical or managerial fixes. In some cases, they depend on pricing to produce market shifts. They do not address the root of the problem.

Mr. Kothari provided a pertinent example. Replacing 100 fossil fuel vehicles by 100 electric vehicles will not change the situation much. It will result in other kinds of destructive mining and destruction of natural ecosystems. Moreover, private electric vehicles can be afforded only by the rich.

To save the environment, we need to reimagine transportation. Public transport should be the way forward. As Gustavo Petro has mentioned,” A developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It is one where the rich use public transportation.”

Alternatives

There are two alternatives.

One is resistance: to say no to destructive projects and to the structures and institutions that promote them. A good example is Adivasis (Indigenous or tribal peoples) protesting against two large hydroelectric projects on the Indravati river in central India. (See figure below.) The Adivasis knew they would be displaced due to the project and the government would do little to rehabilitate them. Moreover, the Adivasis considered the river their mother, whereas the government looked at it as a commodity, a source of energy. In our traditional civilizations, nature is treated as something sacred, not as something to be exploited.

But the other alternative is to pursue the right kind of economic and social well-being. People have needs, and there is a need for an economy that provides for them, as an alternative to ‘development’ that focuses primarily on economic growth. I can give a number of examples of such an approach.

Deccan Development Society (DDS)

Deccan Development Society (DDS), set up in 1983, is a grassroots organization working with nearly 5000 Dalit and indigenous small farmer women in sanghams (village level voluntary associations) in the Zaheerabad region of Telangana. Facing hunger, malnutrition and poverty, these women came together to deal with the challenge of food insecurity, as also caste and gender discrimination.

Today, DDS strives for just and sustainable well-being, and to assert the sanghams’ autonomy in multiple spheres like food, nutrition, seeds, marketing, etc. DDS has attempted to revive traditional knowledge in farming and seeds for crops such as millets (jawar, bajra, ragi, etc) and local rice and pulse varities, and advocated for the inclusion of this knowledge in the public food policy systems. This has ensured food security as also food sovereignty (complete community control) for the 5000 families.

DDS is a testament to a revitalized rural community with abundant locally grown, nutrient-rich food produced through regenerative agricultural practices. This vision is rooted in the principles of a regenerative economy, and women's empowerment.

RojavaThere are about 40 million Kurds in central/western Asia. They have been a persecuted group in all the nation-states they are part of (Iran, Iraq, Turkey, Syria). Today, they are fighting for autonomy and self-governance.

The Kurdish women's movement, basing its struggle on the ideology if ‘jineoloji’ (science of women’s revolution), is at the heart of one of the most revolutionary experiments in the world today: Rojava in N-E Syria. Forged over decades of struggle, ncluding in the fight against ISIS, Rojava embodies a radical commitment to ecology, democracy and women's liberation.

Kuneria, Kutch

This is an outstanding example of success in a village of non-adivasis (close to Bhuj). On all the factors of well-being, the panchayat is doing extremely well. A Balika panchayat (girl’s council) has been set up to focus on the issues of young girls. The government schools are so well run that some private schools have closed. Water harvesting is done to conserve water, making the region self-sufficient. Forest regeneration is happening. There was no impact on the local economy even during Covid. Employment continued under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, and people could earn their livelihood.

Bhuj

The Bhuj urban transformation project, called Homes in the City, is aimed at mobilising people to be a central part of planning a city. Poor people living in the area were not able to get decent housing, or other civic amenities they should have access to including water and sanitation. They mobilised, with the help of five civil society organisations, to struggle for land rights, create them own plans for dignified living, achieve decentralised water security, and safety for women.

Europe

Mr Kothari provided several examples from Europe. A factory in Greece is owned and run democratically by the workers, and all workers get the same wage per hour of work regardless of their functions and tasks. A school in Greece provides high quality affordable education but with low fees. This is because it has cut down costs sharply through the volunteering efforts of the local community in a process called ‘time-banking’. Many communes in Germany are trying to share resources and living conditions, rather than live individualised, atomised lives where each family or person has their own car, washing machine, etc.

Education

The Indian education system has traditionally been straitjacketed with an excessive focus on cramming and reproducing things from memory in exams. The so-called public schools are actually run by private organizations and simply unaffordable to the common man.

Education should be more meaningful where students learn to work with their hands and the heart in addition to the mind. Education should also be affordable and inclusive, and connect young people to their own communities, to nature, while also learning from cultures worldwide. Mr Kothari provided some outstanding examples in this context, including:

• SECMOL

From its founding 1988 by Sonam Wangchuck, one of SECMOL’s main objectives has been to improve the educational system of Ladakh. In 1994 SECMOL launched the Operation New Hope movement to improve education in Leh District. SECMOL has made education more meaningful, enjoyable, creative and inclusive. Original batch of students of SECMOL were school dropouts. But quite a few of them have gone on to become leaders in their fields such as film making and organic foods.

• Marudam

Marudam School (near Madurai) is located on an organic farm and spread over 12 acres. Land is something the school takes seriously. Students care for, and constantly engage with land as a rich, real-life, educational resource, integral to the learning process. They are trained to embrace a simple, environmentally conscious and cost-effective lifestyle, and to do things as collectives rather than strive for individualistic, selfish pathways.

Communication, Arts and technology

Here the aim is to move away from government and corporate control, which mainstream media is unfortunately in the stranglehold of. Examples of more democratically run, people-based media are:

- People’s tech innovations, opensource, copyleft

- Community radio (e.g. Dalit Radio run by women of DDS, described above)

- Movement newsletters, folk theatre

- Participatory film/video (e.g. Green Hub)

- Internet (e.g. Scroll, Wire, News Laundry …)

- ‘Social’ networks … virtual communities

Framework for transformation

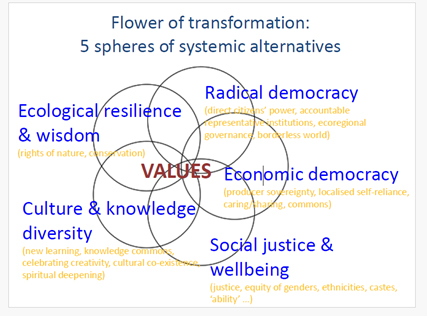

What is the common thread running through these success stories? We can see it as a flower with five spheres of life as petals, and a core of values:

Radical Democracy: The essence of a democracy is not elections. Rather it is power being held by people through their own collectives. Decisions are made primarily by grassroots communities (rural and urban), not by the government or bureaucrats, but in so far as a govt exists, it is made accountable.

Economic democracy: The economy should be run for the people and by the people. The means of production and the profits belong to the people, not to the big corporations or the government. We must go beyond GDP as an indicator of development and look at parameters of well-being such as clean air, clean water and good food. The enormous contribution of nature, and of women, to the economy should be visibilised, and relations of caring and sharing brought back centre-stage.

Social justice: Casteism, patriarchy/gender inequality, and so on have no place in a well-being society, so struggles against these and other inequities and discrimination including against the so-called ‘disabled’, or ethnic / religious minorities.

Culture/knowledge diversity: The colonial education system emphasised modern science to the exclusion of everything else, and also homogenised cultures (including language, cuisines, etc). We must take pride in our indigenous knowledge and cultural systems, and sustain or revive them, while bringing in necessary reforms for social justice. For example, we have several indigenous systems of medicine such as unani, ayurveda, Tibetan, and many folks traditions.

Ecological resilience: We must re-integrate ourselves within nature, respect its integrity & rights, and the spiritual connections with all life. We should not think of ourselves as sitting on top of nature. Rather, we should coexist with nature.

Putting these five spheres together, we must advocate Bioregionalism. We must reimagine the governance of South Asia and look beyond the nation-state boundaries. For example, countries should not be building dams on rivers and diverting the water for their own use, making downstream countries or peoples suffer. India’s hydroelectric projects on the Ganges and Indus have reduced the availability of water to Bangladesh and Pakistan respectively. China is now building dams that will reduce the availability of water for India. A biocultural-regional approach will re-establish the flows of nature, and of cultures and small-producer based trade.

Values and Ethics

Transformations such as the ones described above, are guided by the following values:

- Diversity and pluralism of ideas, knowledge, ecologies, economies, ideologies, cultures)

- Self-reliance for basic needs (swavalamban)

- Self-governance / autonomy (swashasan / swaraj)

- Cooperation, collectivity, solidarity, commons

- Interconnectedness with each other and the rest of nature

- Rights with responsibilities of meaningful participation

- Dignity and creativity of labour (shram)

- Qualitative pursuit of happiness

- Equity / justice / inclusion (sarvodaya)

- Simplicity / sufficiency / enoughness (aparigraha)

- ‘Rights’ of nature / respect for all life forms

- Non-violence, peace, harmony (ahimsa)

- Subsidiarity and ecoregionalism

Essentially, such values are embedded in worldviews and cosmologies that celebrate life, not money, fame and power. One such is Eco-sSwaraj, emerging from the ancient Indian worldview of swaraj (self-rule). This is about achieving human well-being, by empowering all citizens and communities to participate in decision-making, ensuring socio-economic equity and justice, as also respecting other species and the limits of the earth. It is about looking at the community (at various levels) as the basic unit of organisation, not the state or private corporations.

Vikalp Sangam

Vikalp Sangam started in 2014, to explore and bring together alternatives to the current model of ‘development’ as also to structures of capitalism, patriarchy, racism, etc. These include grassroots initiatives for basic needs, direct political and economic democracy, struggles for justice and equality, and against oppression, inequality and unsustainability.

The Vikalp Sangam process includes documentation of alternative initiatives across India, outreach with various kinds of people, physical and online gatherings, and other forms of networking. People share, collaborate, and reflect on their experiences and knowledge, and on this basis build collective visions of a better society. Additionally, the Sangam groups engage in collective advocacy for policy and systemic transformations.

Physical Sangams (confluences) are organised either regionally (state, district or eco-regional level) or thematically (e.g. energy, food, health, democracy). As of 2025, over 30 Sangams havebeen held.

Global Tapestry of alternatives.

The world is going through a crisis of unprecedented global scale. We are seeing deepening inequalities, increasing deprivation, the destruction of ecosystems, catastrophic climate change and ruptures in socio-cultural fabrics. However, there are radical alternatives to this dominant regime. These initiatives champion sustainable and holistic agriculture, community led water/energy/food sovereignty, solidarity and sharing economies, worker control of production facilities and the revival of ancient traditions. The focus is on the emergence of new worldviews that re-establish humanity’s place within nature, as a basis for human dignity and equality.

The Global Tapestry of Alternatives seeks to create solidarity networks and strategic alliances amongst such initiatives, at local, regional and global levels. It has no central structure or control mechanisms. It builds on already existing and new alternatives to dominant regimes. It promotes close and synergistic linkages with existing organizations, like the World Social Forum.

Q&A

As a young high school student in Delhi in the late 1970s, Mr. Kothari and his friends became interested in animal rights and nature. They would go bird watching and take part in nature walks. They were concerned about the rampant destruction of Delhi’s Ridge forest, one of the largest urban forests in the world and the northern-most part of the Aravalli. In a manner of speaking, they are the lungs of Delhi.

The students successfully lobbied for the protection of these forests on the outskirts of Delhi. Mrs. Gandhi, then Prime Minister of India, found merit in the suggestions and the Delhi government passed necessary orders. That is how we see the forest cover even today.

Around the time of this campaign, and to make their efforts more systematic, they decided to form an organization. The name Kalpavriksh, emerging from Indian mythology in which a wish-filfulling tree emerged from the churning of the oceans during a war between good and evil forces, reflects the essential attributes of nature. It is bountiful and can give us what we want.

There are two mistakes we make when it comes to scaling.

Upscaling: We try to do the same things on a bigger scale within the organization. But as we become bigger, the original ideals get diluted, structures become more hierarchical and rigid, and the goals of transformation are lost sight of.

Replication: We pick up an idea from somewhere and try to implement it elsewhere. But the context, processes and challenges may be different. So, we need to understand the principles carefully before applying the same idea in a different context. What is therefore necessary is outscaling, where through such learning, more and more initiatives spring up, then connect across the landscape to create impacts at scale.

Shifts in government policy can also help scaling. For example, if the chemical fertilizer subsidies can be shifted to organic farming, many more farmers will get involved and organic foods production can be scaled up.

Many of the problems we face today are because modern generations aspire for a higher standard of living. These aspirations are shaped by the media. We are being constantly bombarded with messages about what a good life should be.

We should counter with alternative narratives. In the global South we tend to mostly copy the wrong things from the North, such as the definition of ‘development’. If at all we need to learn from it, we should copy good things, such as the growing trend of, cycling to work, which has become aspirational in cities like Amsterdam. These can complement our own knowledge and wisdom generated over millenia, such as for instance the consumption of healthy organic foods and how to live with and within nature.

We should move the cultural markers. This will enable a shift from destructive to a more sustainable way of living.

Product labeling can also help. In the label, we can give details of the people who are making environmentally friendly products and fostering a sustainable way of living. This can enable consumers like us to connect with the producers. These narratives will morph into compelling stories.

How do we prioritize eco over ego? Our education system should impart values to young minds, not through moralistic teaching but through creative methods of nature/community-rooted learning and doing. From the British colonial times till today, schooling has become competitive and individualistic. Rather than encouraging individual achievements, we must focus on youth working collectively, to move their entire batch forward. Learning should also be such as to create a sense of responsibility among students. This way we can reduce the ego and enhance the collective spirit.

Mr. Kothari provided inspiring examples of how cooperation can take precedence over individualism.

Ubuntu: Ubuntu is a southern African philosophy that emphasizes the interconnectedness of people and their responsibilities to each other and the environment. It is often summarized by the phrase, "I am because you are, you are because we are."

Sir Isaac Newton put it another way, to acknowledge the contribution of others rather than emphasizing individual achievement, when he said:” If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

We should teach the importance of nature to children. They should understand that were it not for nature, we would all be dead. Most students understand that oxygen is the most essential item for life. But 95% of school children do not know that oxygen comes from green algae in the oceans. We should appreciate the importance of being within nature, our dependence on nature and acting in ways that protect nature. The schooling system is not imparting the most important knowledge, i.e. knowledge about nature.

Marudham: Located near Madurai, the school is an outstanding example of inclusive education (as mentioned earlier). In this school, there is active involvement of students and faculty in developing the curriculum. There is an emphasis on outdoor learning in the fields from farmers and working with one’s own hands.

No transformation can succeed without women empowering themselves. So, gender equality is extremely important. Either women must lead the transformation or form the core of the initiative.

The Forest Rights Act 2006 is the result of widespread protests by Adivasi and non-Adivasi Forest villages who were facing evictions from lands they were occupying or cultivating. Before this Act, forest-dependent communities, especially Scheduled Tribes (STs) and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (OTFDs), did not have official recognition of their rights to access or manage forest land and resources.

Mendha Lekha, a village in the Gadchiroli district of Maharashtra, became the first village to get community rights. The villagers insisted that the transit permits (for example while moving bamboo) should be issued by the villagers rather than forest department officials. As a result, gram sabhas across the country became empowered to issue transit permits.

When sustainability and environment become fashionable and the domain of the rich/elite, it becomes self-destructive. The outcome is premium pricing and lack of affordability. How can we make organic food available at reasonable prices to the common man?

There are success stories to inspire us. The Dalit women of DDS have linked up with families in Hyderabad. These families contribute Rs 10,000 every year upfront. In return they get good quality organic food. This kind of a direct relationship between farmers and consumers is useful and can eliminate the middlemen (such as corporate-run organic foods shops) who are often the main reason for the high prices. The government can play a big role here but only if it is enabling, rather than interfering.

The same model can also be applied to handmade textile producers. We should enable the handloom weavers to make a direct connection with consumers. Ela Bhatt’s SEWA (Self Employed Women’s Association) works with women to create affordable products. When it comes to schools, Marudham is a good example. With such initiatives, we can make goods and services affordable and eliminate the elitism associated with green initiatives.

Unfortunately, the current economic system subsidizes the industries which are severely damaging the environment. Petrol is subsidized but paper is not. That is why we see more plastic packaging (even for organic products) rather than paper packaging which is far more environment friendly.

If we simply focus on news going around in the media, we will get depressed. Instead of only criticizing the wrong doings and staging protests (which remains important, of course), we should also focus on communities who are finding solutions despite the challenges they face. We are privileged people. If these underprivileged people are hopeful and can fight their way, why should we lose hope?

We should also spend time with nature. The leaves, flowers, fruits and the birds can cheer us up.

Lastly, our ancient religions and philosophies teach us that when we feel we have a duty and a passion to do something, we should do it without worrying about the consequences. Instead of worrying about the results, we should just go ahead and do what we think is right. Mr. Kothari goes about his work without worrying about results, though of course he tries to do whatever is necessary to obtain them.