An evening with Mr Abhay Deshpande

Introduction

On Friday, August 30, we had an engaging WiseViews session by Mr Abhay Deshpande, a serial entrepreneur and the founder of Recykal, India’s first sustainable circular economy company. Mr Deshpande’s vision is to recycle 10% of India’s waste and turn it into something valuable. He is well on his way to achieving his vision, with big names like Samsung, Coca-Cola, and Unilever already on board. During the session, Mr Deshpande narrated his journey as an entrepreneur, the challenges he has faced and his future plans.

About Mr Abhay Deshpande

Mr Abhay Deshpande is a distinguished serial entrepreneur whose innovative mindset, leadership capabilities, and expertise in digital marketplaces have resulted in a remarkable career spanning two decades.

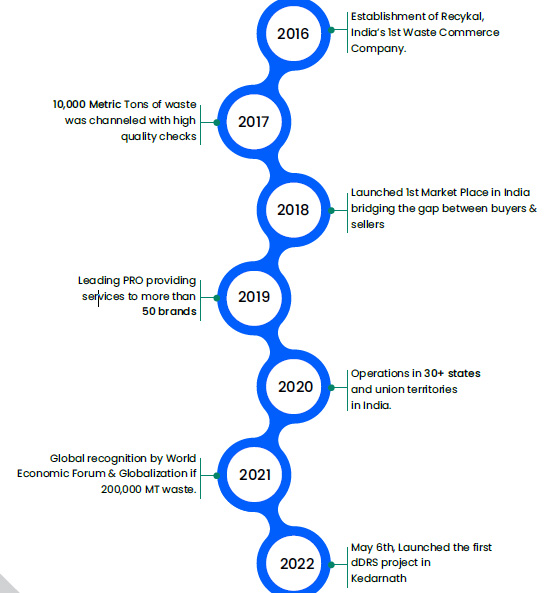

Mr Deshpande is the Founder of Recykal, a clean-tech company established in 2016 to foster a circular economy. He has reshaped the conversation around waste management and recycling with his vision to mainstream sustainability, Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) practices and circularity.

Before Recykal, Mr Deshpande was the driving force behind Martjack, India's first Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) company specializing in enterprise e-commerce platforms. Founded in 2007, Martjack was acquired by Capillary Technologies in 2015. This marked one of the largest SaaS deals in India at the time.

Mr Deshpande started his entrepreneurial journey in 1998 with Malamall.com, recognized as one of India's pioneering e-commerce ventures. This initiative was an early indicator of his foresight and adaptability, which continue to define his career.

Whether in the boardroom or at industry events, Mr Deshpande brings a fresh perspective, inspiring others to think differently about the role of business in society.

Mr Deshpande’s entrepreneurial journey

Mr Deshpande, hails from Partur, a small village in Maharashtra. He courageously chose to chart the untrodden path of an entrepreneur, becoming the first person in his family to do so. That is indeed remarkable, considering that his Brahmin, middle-class family was dominated by government servants. For Mr Deshpande the early years were indeed a big struggle. As he put it, this phase was all about managing rejections. But these rejections only made him stronger and wiser.

Malamall (1998-2006)

Malamall, Mr Deshpande’s first venture, got its name from a Naseeruddin Shah movie. The idea came to Mr Deshpande when during train journeys, he saw people carrying the famous Karachi bakery biscuits from Hyderabad to Pune. What if such products could be directly delivered to the homes of consumers?

Malamall was the first marketplace in India where one could find retailers who made speciality products – be it eatables or fashion or apparel. Mr Deshpande aggregated those products in one place and made them available to people in any part of the world. Malamall enrolled 100,000 users in the US and the UK. The venture enabled 45,000 Rakhis to be shipped to US & UK. It was probably India’s first online marketplace.

Malamall was probably 10 years ahead of its time. (Internet connections were not easily available those days in India.) Contrary to what the name sounded, the media publicity and Mr Deshpande’s persistent and courageous efforts, the venture did not make much money. Few understood ecommerce those days. As he joked, “Having spent eight years in ecommerce, knowledge-wise I had become maalamaal but not money-wise.”

For Mr Deshpande, it was indeed hard work with little money flowing in. As one media report mentioned, even on day 2 of Mr Deshpande’s marriage, he was working till 2 am. He never took holidays for 17 years. Mr Deshpande struggled to own a home and drove a second-hand car. He had to sell old newspapers to pay household bills. He was thrown out of his rented accommodation for not being able to make rent on time. Mr Deshpande also defaulted in paying his daughter’s school fees, twice. Many times, he was cash-strapped to pay salaries of his employees. Often, his phone/Internet connections were disconnected due to non-payment of dues.

https://inc42.com/buzz/martjack-abhay-deshpande/

Despite the failure, Mr Deshpande did not lose heart. As he put it, there are no failed entrepreneurs. There are only learned entrepreneurs.

Mr Deshpande also learnt some important lessons: have the right talent (Malamall was full of friends and relatives.), a solid team which will stick with you even during tough times and learn to say no.

Martjack (2007-2015)

By 2006, the attitude towards commerce had begun to change. Many of the brands who were on Malamall started asking him for options to start their own ecommerce site or store. That’s where Mr Deshpande sensed another opportunity: to provide the technology to enable retailers to build their own sites. These retailers would never be able to assemble the talent to handle technology on their own.

Mr Deshpande’s second venture was Martjack, India’s first SaaS (software as a service) platform. The concept of SaaS was not well known those days. The use of pirated software was rampant and paying monthly for software was not appealing! Looking back, Mr Deshpande feels that like Malamall, this venture too was ahead of its time by about 4 years.

It was not easy sailing. Martjack was essentially Made in India for the global market. The Satyam debacle in 2009 created problems and a perception issue especially for Hyderabad where the venture was headquartered.

Initially, Mr Deshpande focused on the Small and Medium Business segment. The first customer did not generate revenues of even Rs 4800 annually. It was in 2009 that MartJack started getting good traction, mainly due to Gitanjali Gems, MartJack’s first enterprise customer.

Martjack onboarded close to 2,000 merchants by 2012. But Mr Deshpande realised that enterprise SaaS was where the big opportunity lay. Hence, in 2013, the firm changed gears to focus on enterprises only. Bigger clients fell into its lap like Future Group and Walmart India. By the end of 2013, Martjack had transformed into an enterprise platform, growing from a 30-member team to a 150-member enterprise. The last customer Martjack acquired, billed Rs 69 lakhs per month. Compare that with the first customer who paid Rs 399!

The venture existed for 100 months and raised $ 7 million (about Rs 42 crores) from 86 investors in 135 tranches across 22 cities in 11 countries. They were all unknown people who were attracted by the promise of the idea.

Martjack was finally acquired by Capillary Technologies of Singapore in 2015. Mr Deshpande feels gratified that the venture benefited 176 people and created five dollar millionaires and 25 crorepatis. Even his driver made Rs 10 lakhs and became an Ola entrepreneur. All the 86 investors also benefited.

Recykal

After his exit from Martjack, Mr Deshpande decided to take a break of 6 months. But on the 6th day of the vacation, it became clear that neither he nor his family members liked the idea. He thought of becoming an angel investor but realized that his heart was in entrepreneurship. He was soon thinking about the next big opportunity. From an investor, he went back to becoming an entrepreneur. That is how the idea of entering the waste recycling business came.

Mr Deshpande built a strong team. During 2017 and 2018, they spent time learning about the waste recycling space. They started with a 2-year ground research, on landfills and waste generating entities. These were their key learnings:

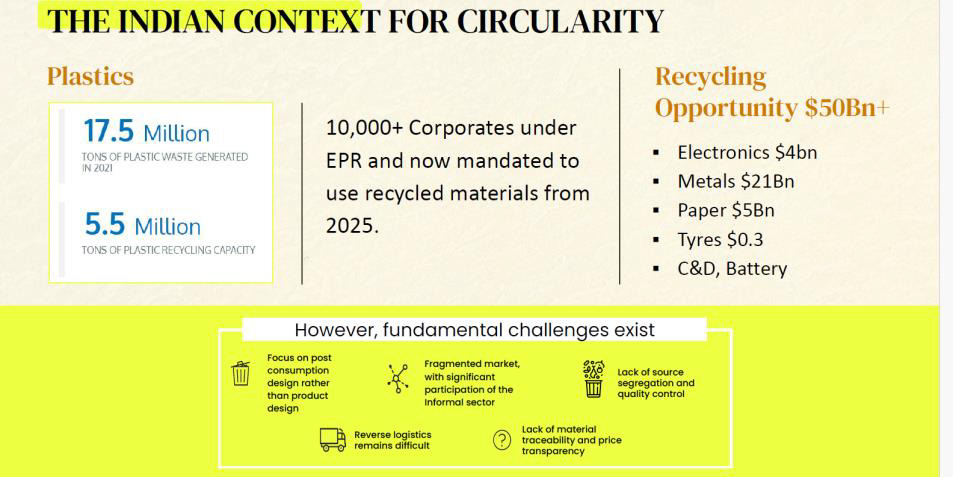

- India recycled approximately 60% of plastic waste, with the remaining 40% being disposed of in landfills. (according to a Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) report in 2019).

- Unmanaged plastic waste leakage increased toxicity and caused a negative impact on the environment and the health of people.

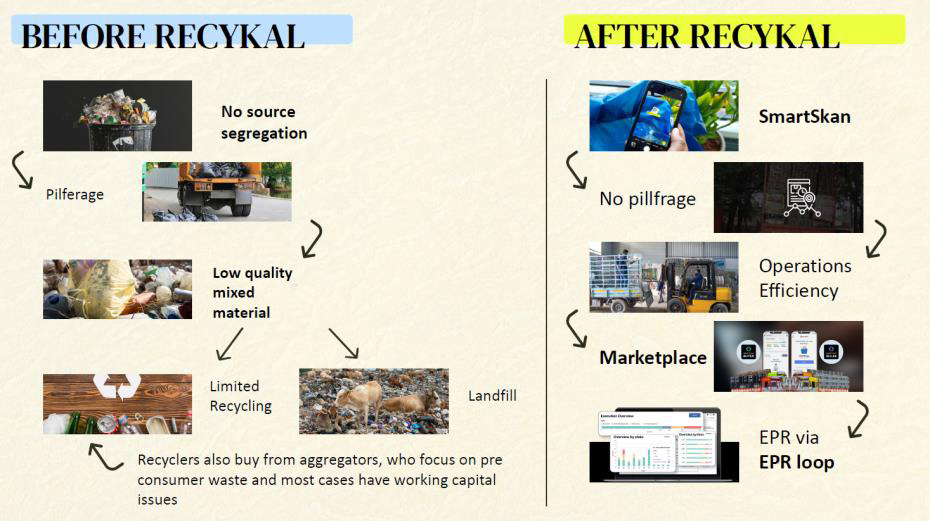

- The waste collection industry had a bad reputation, was run by mafias and was largely unorganized. People worked in the sector without incentives, financial security, and other employee benefits.

By 2018, Mr Deshpande and his team saw a big opportunity to formalise what was largely an informal business. From 2019, the process of monetizing the idea began.

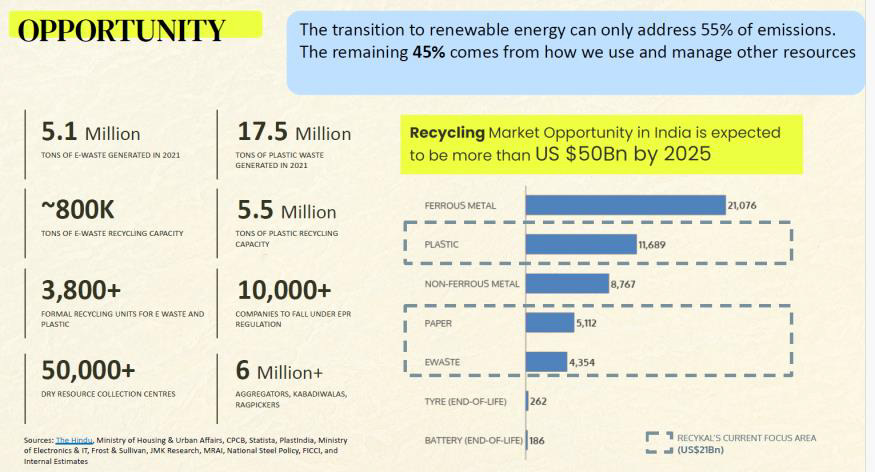

The vision of Recykal was to build a self-sustaining circular economy in India. Recykal decided to bridge the gap between sellers and buyers to efficiently channel demand and supply of recyclable waste by offering scalable digital solutions and tools.

Achieving Recykal’s vision meant driving behavioural change among three major stakeholder groups: government, ragpickers and consumers. The government had to move its focus away from garbage collection and dumping it in landfills. The ragpickers had to become a part of the formal economy. Consumers who just dumped plastic and other material had to look at waste as a source of value.

Mr Deshpande provided some pertinent examples. We read newspapers and carefully preserve them and sell them at the end of the month. We know that paper is valuable. But we throw away plastics which are more valuable. Similarly, we keep our old mobile phones with us and think they will be of some use some day.

Making people see value in plastics is all about behavioural change. Mr Deshpande feels that behavioural change is possible in two ways: Fear and greed. Fear can only be enforced by the authorities. But we can pander to greed through incentives backed by technology solutions. That is how the digital deposit return scheme started: paying people when they return used plastic bottles.

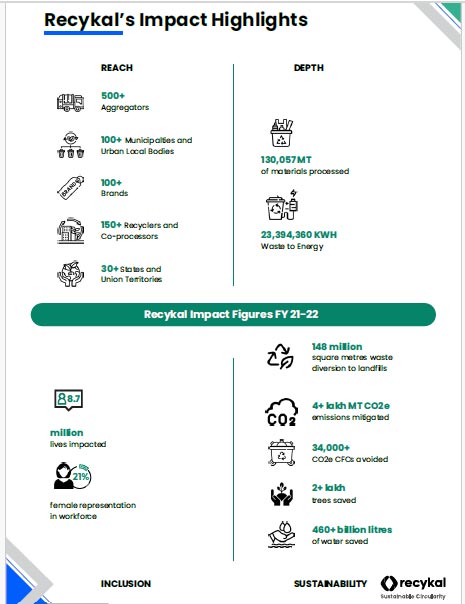

In a matter of 2 years, the business scaled from 2 states to 30+ States and UTs. Last year, 800,000 tonnes of waste were recycled using the platform. This year, some 1.2 million tonnes of waste will be recycled back into the circular economy. The target for 2027-28 is 6 million tonnes (10% of the total waste generated in the country).

Recykal has almost achieved $ 100 million topline. The company is covering metals, paper, tyres, batteries besides plastics.

Currently, there is a 450 member team based in Hyderabad. Funding ($ 45 mn) has come from famous names like Morgan Stanley, Mr Ranjan Pai, Mr Ajay Parikh of Pidilite and Mr Vellayan of Murugappa.

Concluding remarks

Here are Mr Deshpande’s top 5 lessons:

- Dream big and pivot based on market needs.

- Rejections are an inseparable part of an entrepreneur's life.

- Be positive and learn to manage rejections.

- Build Trust.

- Hire an “A” Team.

- Entrepreneurship is a journey. There is no finish line.

Q&A

Government policies and right behaviours are both needed to drive large scale change. In 2015-2106, the government introduced legislation to enforce Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). Under EPR, producers began to bear substantial financial and/or physical obligation for the treatment or disposal of post-consumer products.

Till then, brands were not concerned about what happened upstream or downstream. Take the case of beverage companies. They did not bother about what happened to the plastic bottles after the beverage had been consumed. Now, they have the responsibility for recycling used plastic bottles. In short, under EPR, producers/brand owners must internalize the costs of handling waste. From plastics, the concept is now being extended to paper, used oil, batteries, tyres, metals, etc. We may even see it extended to textiles.

The legislation covers rules for proper collection, segregation, and channelisation of plastic waste throughout the value chain in India. In addition, the rules specify the roles and responsibilities of the various stakeholders. For example, the municipal authorities (by themselves or in collaboration with producers) must provide the necessary infrastructure for the segregation, collection, storage, transportation, processing, and disposal of plastic waste. All plastic manufacturers and recyclers must register with state pollution control boards. Moreover, charges on carry bags must be explicitly imposed. The revenue generated by the authority needs to be utilised entirely for waste management.

It will be difficult for brands to handle the process of waste collection themselves. They would need the help of various service providers. Technology platforms will have a big role to play. There are several opportunities for entrepreneurs to innovate in this new dispensation.

Mr Deshpande mentioned that the next two decades will belong to sustainability. With society looking for numbers and impact, the action has moved far beyond presentations. Indeed, sustainability is the need of the hour to save our planet. We will see many solutions and entrepreneurs emerging in this space.

Recykal acts as a circularity partner for corporates and streamlines the process of handling of waste. The company is collaborating with the largest FMCG companies, plastic producers, importers and brand owners to help them meet their EPR targets for recyclable and non-recyclable plastic waste. This involves collection, segregation, and recycling of specified amounts of waste through a CPCB (Central Pollution Control Board) registered recycler.

Recykal provides end-to-end traceability with transparency in prices, material availability and quality through its innovative solutions and web applications. Recykal provides data access to corporations and waste generators/processors at every stage of the value chain, until the entire waste is recycled, recovered, or disposed of in landfills. This makes it easier to validate claims that a company is taking sustainability seriously. Recykal provides education for employees on sustainability.

This is one of the big success stories for Recykal. The company has been working for 5 years on this project. It is a classic example of driving large scale behavioural change with incentives using a tech platform.

The renowned Kedarnath shrine in Uttarakhand experienced a surge of around 50,000 daily visitors in 2022 after a two-year break due to Covid. However, this influx led to widespread littering. The problem attracted public attention when the Prime Minister referred to this littering in his Mann ki Baat. The local District Magistrate promptly reached out to Recykal.

A Digital Deposit Return System (dDRS) has been implemented on the stretch from Rudra Prayag to the temple. For each bottle costing Rs 20, a deposit of Rs 10 is collected. The money is given back when the bottle is returned.

Initially, there was a poor response but soon the efforts paid off. Last year, 16 lakh bottles were collected. Now the target is 5 million. Already 2.5 million bottles have been collected. Even if people throw bottles, we can be sure that the rag picker will retrieve them and collect the money! The scheme has been extended to Gangotri, Yamunotri, Badrinath, the other holy sites that together form Char Dham.

The deposit return system is not new and is being practised in some 45 countries. To be successful it should be backed by technology. Government backing is also needed. The initiative must be implemented at the state level so that all are on board.

There is a plan for making it mandatory for all products sold in the area to have QR code stickers across outlets. Additionally, 20 collection-cum-refund points will be established to ensure the proper channelization of waste. Campaigns will be conducted to engage all stakeholders, ensuring their mandatory adoption and enhancing communication and awareness. dDRS will also be implemented in Nainital at the Urban Local Body level, with the establishment of over 200 manual collection points. This initiative aims to recycle an estimated Rs 50 Crore+ worth of plastic material annually.

Goa has become the first state to introduce legislation to implement the dDRS. Every product sold in the state will carry a deposit. Mr Deshpande is convinced that dDRS will be a game changer for solving the littering problem.

Uttarakhand is also likely to take a leaf out of Goa’s book and pass legislation. We will soon see people in Goa and Uttarakhand putting all their waste in a cardboard box. Other states also may follow the examples of these two states. This is excellent for recycling. It is high quality material, very much amenable to recycling, compared to material retrieved from a waste basket.

Each country has its own ecosystem. For example, in developed countries people pay for waste handling. They don’t expect any money. In fact, developed countries have used their financial muscle to use developing countries as dumping grounds for their waste. In India (and other southeast Asian countries), we do not discard things easily. We keep using them for as long as we can. So, India in some ways, is ahead of the curve.

We need home grown solutions. We must use technology to our advantage. Reverse vending machines will not work in India. They may get stolen. We need digital solutions. The success of UPI shows that we must use our mobile phones as reverse vending machines. But we must move away from a jugaad approach to a more serious, process, driven approach. If we get our act right, we can become global leaders in recycling.

The Indian legislation is clear. Hazardous waste (medical, chemical, pesticides, etc) cannot be recycled. It must be incinerated. Yet some farmers are throwing away these containers carelessly. Animals are dying and the environment is getting degraded as a result. We need incentives (deposit return schemes) and a better recycling infrastructure to prevent this.

One participant mentioned that incineration has not taken off in the country. What can we do about it? Mr Deshpande remarked that incineration should not be the preferred solution. In incineration, we are burning the materials and there are side effects. We should use incineration only for hazardous waste.

Wherever possible, we must encourage recycling. This is especially so for plastics in general. We must also move away from non-recyclable to recyclable materials and from down cycling to upcycling. Bottles are currently being melted used to make yarn. That is an example of downcycling. They should be reused to store beverages. Upcycling creates more value.

NHAI (National Highway Authority of India) is encouraging the use of recycled plastics for road construction. Pilots and trials are already happening. But economic viability has not been conclusively established. The quality and consistency of the material should meet the required standards for the solution to scale up. We should use non-recyclable material here. Recyclable material can be put to better use.

Rag pickers play a big role. Some 1.5% of India’s population depends for their daily bread on the income of the rag pickers. 80% of them belong to the bottom of the pyramid. The Safai-mitras work in hazardous conditions, without any safety harnesses or kit, to make a living and provide for their family. There is neither certainty of income nor job security.

Mr Deshpande feels that we need to find ways to move the rag pickers up the income strata and ensure their children do not have to do the same job. We need to provide the children education. Mr Deshpande’s target is to bring one million rag pickers into the formal sector. Recykal is contributing to formalising this sector by assisting safai-mitras with registration as well as achieving a social identity and expression so that others can recognise their efforts and hardships.

It is heartening to note that many CSR initiatives are being launched to help these people. Recykal is working closely with JSW, Mondelez and other corporates.

Recykal is also trying to raise awareness among safai-mitras about the types of waste that have more value in the recycling industry and can generate higher income. Recykal is also educating them about which materials are hazardous and can endanger their health.

North India, especially is prone to smog as farmers burn a lot of agricultural waste. Mr Deshpande is seeing demand for solutions in this area (from companies like IOCL, BPCL). However, we need government policies like EPR. Onboarding many farmers on one platform is not easy. Economic viability must be tested.

Another participant mentioned that in the UAE, there is a good practice of a book bank (a container) for recycling old books and magazines. Since each home will usually have a quite a few old books, this can be a useful initiative. The UAE also has a bottle bank. Such initiatives can enable a more sustainable supply chain

One way to increase formalization of the waste collection sector is to reduce the GST which is currently 18% to the lowest bracket of 5 %. Indeed, this is the biggest stumbling block to formalization. Noone wants to pay 18% tax. Large players like Tata Steel have been advocates in this regard but have not been able to persuade the government.