An evening with Ms Anu Prasad

Introduction

On Friday, March 22, we had an engaging session by Ms Anu Prasad, Founder & CEO of India Leaders for Social Sector (ILSS). During the session, Ms Prasad explored how the social impact sector can help in building a better India. She demystified the complex dynamics of the social impact sector. Ms Prasad emphasized the critical role active citizens can play in shaping its future, through their perspectives and expertise.

About Ms Anu Prasad

In her role as CEO of ILSS, Ms. Anu Prasad is committed to building the leadership talent and capacity that India’s social sector needs to make an impact at scale. She also serves as a mentor to young professionals and senior leaders, sharing her knowledge and expertise (in the corporate and non-profit sectors) and guiding them on their own leadership journeys.

ILSS is not yet an incubator. A not for profit must complete 3 years before it is eligible for institutional funding. ILSS is a Section 8 company focused on building capacity.

Most of the CSR money goes into programs and little into capacity building. ILSS fills the gap and strengthens the people who are doing the work on the ground. ILSS helps social sector founders to raise funds and take care of governance, technology, and compliance issues. ILSS can be described as a leadership institute for the social sector set up to catalyze organizational learning and capacity building. One of the key focus areas of ILSS is to attract corporate talent and bring them to the social sector.

Prior to establishing ILSS in 2017, Ms Prasad served as the founding Deputy Dean of the prestigious Young India Fellowship (YIF) and played a pivotal role in the establishment of Ashoka University, India’s first liberal arts university.

Ms. Prasad’s professional journey includes leadership positions at multinational companies such as American Express and TNT, where she honed her skills in finance and operations. Additionally, she co-founded and managed a successful travel company.

Beyond her professional accomplishments, Ms. Prasad is an avid reader, an active volunteer in civic causes, and a passionate believer in lifelong learning.

India’s development story

Despite all the challenges the country faces, Ms Prasad is optimistic about the future. We have come a long way since independence. Consider the following statistics:

- In 1950, we were a $ 30 bn economy. In 2025, our GDP will be about $ 5 trillion.

- In 1950, life expectancy was 34. Today, it is about 69.

- In 1950, the literacy rate was 20 %. Today, it is about 74%.

- In 1950, the under 5 mortality rate was 26%. In 2019, it was down to about 3.4%.

- In 1947, we only had 20,000 km of highways. Today, we have 120,000.

Gender inequality is a major concern with a women’s labour force participation rate of only 27.4%. About 74% of the girls do not move on to do higher education mainly because they are worried about safety. Absence of toilets is also an issue.

The heavy wealth inequality is another major concern. Educational outcomes are also lagging. (But the NEP is full of good ideas and has put in place a good framework for improving the quality of education.) On the Global Hunger index (2022) we rank 107 out of 121. We have the largest no of tuberculosis patients in the world.

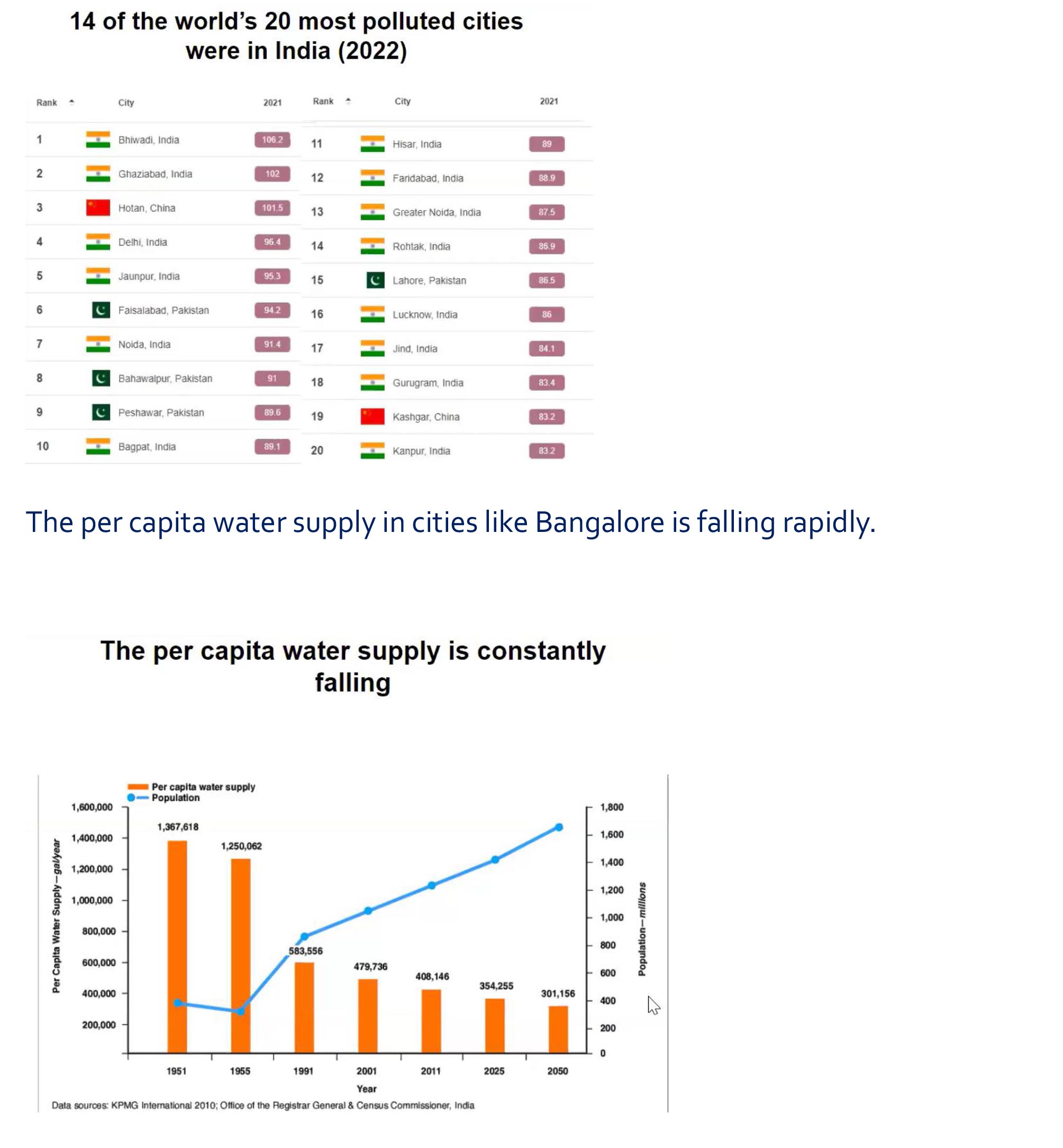

A climate crisis is looming. We have 14 of the 20 most polluted cities in the world. There is heavy pollution in cities like Delhi and Gurgaon.

Decoding the Social Impact sector

There are three main components: Samaj (society), Bazar (market) and Sarkar (government). The three must work together. Markets are often good at coming up with cost effective, scalable solutions. Where markets fail, civil society must step in. Often the civil society establishes a prototype of a solution to the problem. The government can then step in with funding and policies that enable scaling.

Civil Society

The civil society must step up. There are excellent examples of the role Samaj can play. During Covid, we saw civil society providing meals, making arrangements for transportation of migrant workers and supplying oxygen cylinders.

MGNREGA: The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 came into being because Jean Dreze and others in civil society drafted and advocated for it. MGNREGA aims to enhance livelihood security in rural areas by providing at least 100 days of wage employment in a financial year to at least one member of every household. Women are guaranteed one third of the jobs made available under the MGNREGA. Through this work, MGNREGA aims to create durable assets such as roads, canals, ponds and wells. Employment is provided within 5 km of an applicant's residence. Minimum wages are to be paid. If work is not provided within 15 days of applying, applicants are entitled to an unemployment allowance.

ASHA workers: One of the key components of the National Rural Health Mission is to provide every village in the country with a trained female community health activist ASHA or Accredited Social Health Activist. These activists are selected from the village itself and accountable to it. They work as an interface between the community and the public health system. ASHA workers are chosen through a rigorous process of selection involving various community groups, self-help groups, Anganwadi Institutions, the Block Nodal officer, District Nodal officer, the village Health Committee and the Gram Sabha. These workers undergo a series of training interventions to acquire the necessary knowledge, skills, and confidence for performing her role. They receive performance-based incentives for promoting universal immunization, referral, and escort services for Reproductive & Child Health (RCH) and other healthcare programmes, and construction of household toilets.

EMRI: The Emergency Management and Research Institute (EMRI) was set up in 2004. EMRI has woven together the latest telecommunication, computing, medical, and transportation technologies to provide affordable emergency services in tribal, rural, and urban areas. Many Indians face emergencies but either don’t recognize them as such or have nowhere to call. Besides providing a number to call, EMRI has developed programs to teach Indians to recognize and react to emergencies.

EMRI has designed its ambulances, trained its paramedics, and built a unique information and communications technology infrastructure. At the heart of that infrastructure is a computer network supported by a call center. in each state, operators receive emergency calls and direct 4,000 field staff members to respond to them. The Emergency Relief Operators follow a clear process to determine if a call is an emergency and, if so, whether it is a medical, police, or fire emergency. The goal is to help victims survive the golden hour, the first 60 minutes, since 80% of deaths in hospitals take place in the first hour of admission.

SDGs

In 2015, the UN adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a universal call for action to eliminate poverty and protect the environment. When it comes to the implementation of SDGs, India is lagging. The country ranks 112 out of 166. We trail even the neighbouring countries.

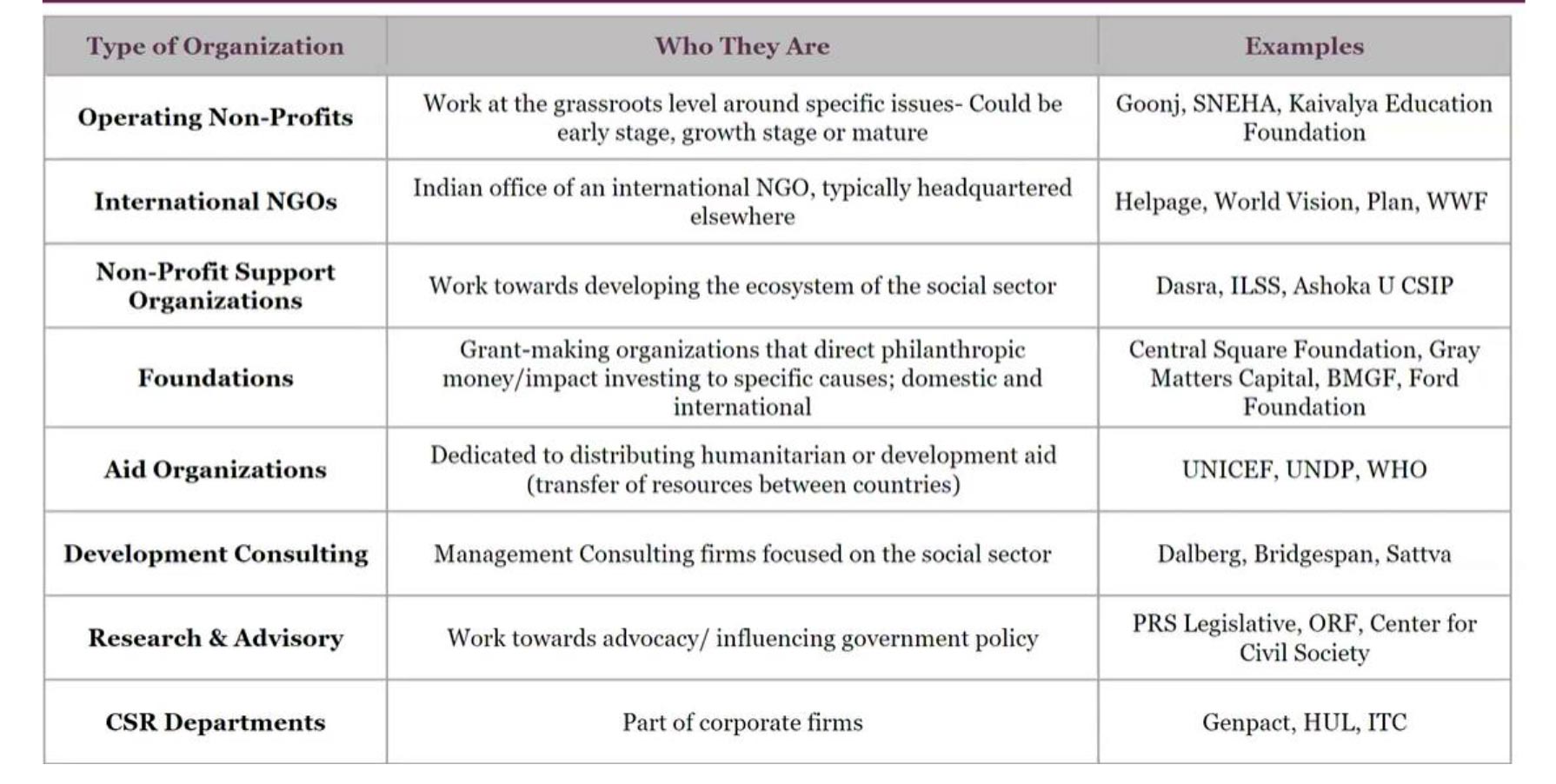

Kinds of organizations in the social sector.

The social sector is not homogenous. There are many types of organizations playing different roles, structured in different ways, with their own priorities and focus areas. Pl see table below.

Systemic Issues

For the social sector to make an impact, the following must be kept in mind:

- Intersectionality of issues: Overlap among different development goals. A long-term holistic outlook is needed.

- Complex problems with long lead time for impact: It may take decades for change to happen.

- The interplay of Samaaj-Sarkaar-Bazaar (Civil Society-State-Markets): The three have to work together.

Funding and Regulatory Environment

- Enduring challenge of raising (quality) funding: Funding is always a challenge for the social sector. Many NGOs are dependent on Programmatic funding and not institutional funding.

- Tax certifications and reporting (12A, 80G, FCRA): Many NGOs struggle here.

- Broader distrust for Social Purpose Organizations, particularly for international organizations: We need to change the perception about NGOs and celebrate the good work.

The Talent Gap

- Talent: It is difficult to attract and retain talent. The social impact sector is not the career of choice for many talented people.

- Funding: Most funding supports programs, not capacity.

- Perception: There are various preconceptions and notions about social sector. The good work done by the sector is under appreciated.

Finding our Ikigai

This is important irrespective of whether we work in the social impact sector or not. We should be working in an area which we are passionate about and where we can make an impact. Every day, when we go to work, we should be charged and energized. For some of us, the social sector may be the place to find our Ikigai.

How we can contribute

If we have corporate experience, we can contribute in many ways other than giving money:

- Systems, processes, tools, and technology

- Scaling up solutions

- Networks and resources

- Complementary perspectives

- Management frameworks and Leadership

- Functional Expertise

Making the shift: Desired behaviours and Role models

Compared to the corporate sector, the social sector is harder and more complex. But it is a career worth pursuing. To succeed, we must have humility, learnability, and willingness to unlearn. Indeed, these are the qualities Ms Prasad looks for when interviewing candidates. The social sector should also not be equated with a retirement job. It involves a lot of hard work. Arrogance has no place in the social sector.

Here are some people who have successfully made the shift and are thriving in the social sector.

The corporate sector can make us hardwired. If we come with the saviour complex, i.e. we have the solution to the problem, it will not help. Indeed, this kind of an attitude can backfire and lead to a lot of damage. There are many examples of hurriedly conceived solutions having a bad impact on society.

Recalling the freedom struggle

Ms Prasad drew a parallel with the freedom struggle. The leaders dreamed of a better India and fought for it. Similarly, we can leverage the social sector to work for a better India. In the next 25 years, we must strive to make India free from poverty and hunger.

Ms Prasad hopes that every citizen will be an engaged citizen and contribute to this progress. People should wear the societal lens and understand societal issues. There is still a lot of work to do: wealth inequality, gender inequality, etc. But we have come a long way since independence and can be optimistic. If we are not optimistic, we will tend to give up too easily.

On how she made the shift

When Ashoka University was being set up in 2010/2011, Ms Prasad was one of the first to come onboard. The university was conceived of as the Harvard of India, the country’s first liberal arts university. The founding team proved that with grit and determination, anything was possible. Today, Ashoka is a household name (though not even 10 years old) and people understand the meaning of the term, Liberal Arts.

While at Ashoka, Ms Prasad observed that millennials were making unconventional choices. They were doing internships with NGOs. So, she decided to dig deeper into the social sector. A lot of money (almost Rs 100,000 crores) was coming into the sector through CSR funds (the 2% contribution). But the absorptive capacity was limited. NGOs with a size of more than Rs 100 crores are rare. Around 2016-17, Ms Prasad wanted to do something for people on the ground. She sensed an opportunity to build the capacity of NGOs: leadership, technology, and finance.

Ms Prasad has always believed in the famous saying: Ask not what the country can do for you. Ask what you can do for the country. In the social impact sector, such opportunities exist.

Today, good solid work is happening in the social sector be it mental health, livelihood, gender, or education. Ms Prasad realized that by bringing senior corporate professionals into the sector, capacity could be built. She has already roped in more than 400 senior corporate leaders. They are put though a structured program. Ms Prasad’s pitch to leaders to be a part of the solution is: If not now, then when, If not you, then who?

Social sector and Climate change: iamgurgaon

iamgurgaon is an initiative led by the citizens of Gurgaon to restore the city’s environment that has been marred by unbridled urbanization. It is an attempt to foster an ecosystem that restores the city’s biodiversity. It tries to boost accountability, consciousness, and vigilance amongst people in order to make Gurgaon, a better and greener place. Iamgurgaon has worked with partners, volunteers and the government on eco-restoration projects involving forests, waterbodies, drains and that were misused as dumping sites and for encroachments.

Social sector and poverty reduction: The Alladin foundation

The Alladin Foundation was created in response to the growing social injustices and human suffering across the world. It champions the cause of the needy.

The Foundation supports small scale projects on girl’s education and women entrepreneurs and promotes literacy and literacy programs with initiatives such as: donation of books and supplies, training of learners, workshops. The Foundation runs campaigns for public health, safe water, children in distress and health education.

The Foundation runs various programs to improve nutrition and encourages community gardens and organic produce. It supports activities such as hydroponic gardens, distribution of food to the needy and community gardening.

Data

Most NGOs are struggling with data. Indeed, there is little data on the social sector. Any initiative to collect data and build credible databases would be welcome.

Social sector and educational institutions

Dr R Prasad felt that the social sector should be built into the higher education curriculum. One of the Admission criteria could be social work. Educational institutions should also do research on the social sector.

Ms Anu Prasad recalled the tremendous impact made by the Young India Fellowship program. It was part of the Chief Minster’s good Governance program in Haryana. The students would interact with the District Magistrate at the district level and with the Chief Minister once in 6 weeks or so. It was seminal work.

It is not easy for most students to take a salary cut and join the social sector. The Mother Theresa Fellowship at Ashoka University was used to boost the income of graduates who wanted to work in the social sector. The extra income for a couple of years gave students staying power till they were able to mobilise funds and stand on their own feet.