Introduction

On Friday, December 19, we had an insightful session by Mr M. Raaja Rajan. He has spent over a decade transforming natural dyeing from a niche, artisanal idea into a scalable industrial reality. Mr Raaja Rajan spoke about the environmental impact of synthetic dyes and why we need to embrace natural dyes.

About Mr M. Raaja Rajan

Mr. M. Raaja Rajan is an industrial engineer by training and a sustainability practitioner by practice.

As Operations In Charge at Natural Dye House and Pure Pigments LLP, Mr Raaja Rajan has pioneered cold-process dyeing techniques for cotton, eliminating the need for heat and significantly reducing energy consumption in textile colouring. His work challenges a long-held assumption in the industry—that natural dyes cannot be scaled without compromising efficiency, consistency, or cost.

Mr Raaja Rajan has led the development of industrial-scale natural dyeing solutions across garments, fabrics, and yarns. This includes adapting natural dyes to jigger dyeing for large-volume production and innovating processes for hank yarn dyeing, enabling natural dyes to move beyond boutique applications into mainstream manufacturing. His innovations have translated into real market outcomes, including the successful execution of large-scale orders of over 20,000 natural-dyed garments, produced in melange yarns for commercial brands.

Earlier, as a Partner at Quality Fibers, Tirupur, Mr Raaja Rajan worked at the intersection of fiber engineering and sustainability, developing natural dyeing techniques at the cotton fiber stage—an approach that required rethinking conventional textile workflows from the ground up.

Mr Raaja Rajan is a recipient of the Government of India’s Department of Science & Technology (DST) – BIRAC BIG grant, for his work in sustainable textile dyeing and the development of natural inks for textile screen printing. This recognition underscores the scientific rigor and scalability of his work.

(BIRAC stands for Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council, a Government of India enterprise under the Department of Biotechnology (DBT). It provides funding (like the Biotechnology Ignition Grant - BIG), mentoring, and support for commercializing biotech ideas.)

Mr Raaja Rajan’s leadership narrative has been shaped by experimentation, constraints, failure, adaptation, and eventual scale. He speaks from lived experience about what sustainability looks like when it collides with production targets, cost pressures, and market realities.

What are natural dyes?

Many people confuse natural dyes with organic dyes and ozo-free dyes. Natural dyes are dyes sourced from natural plant and mineral material. They are found in nature. We can extract these dyes from leaf, bark, seed, root, flowers and vegetable waste.

Why do we need natural dyes?

Textiles make up the second most polluting industry in the world. The environmental impact is felt in the initial, middle and final stages of the supply chain. The current dyeing processes are based completely on synthetic dyes which generate a lot of residual, highly toxic chemicals.

The governments have legislated that companies cannot release the water outside. So, the effluents from the dyeing units are treated and some of the water is taken back for reuse. The remaining water is a complex mix of different chemicals and salts. This water is evaporated resulting in sludge containing complex chemical salts. Every day, a few tons of sludge are being collected across the dyeing clusters, like Tirupur, Karur, Erode, etc. As per government norms the sludge needs to be contained in large concrete tanks, just like nuclear waste. But very soon, all the units run out of these storage spaces. So, they dump it on the roadside or on interior roads or just bury it in the ground. So, these chemicals go back into the groundwater system and into the land.

For example, where Mr Raaja Rajan operates, it was completely agricultural land. The Total Dissolved Solids (TDS), before the dyeing industry came would have been around 200- 300.Currently, in some dyeing areas, the TDS is around 8,500. And where Mr Raaja Rajan is based, it is around 5,500- 6,000. This shows how badly contaminated the groundwater system has become.

Then comes the middle of the supply chain. Globally, around 80 billion textile articles are made like t-shirts, caps, gloves, socks, underwear, bedsheets, etc. When we wash our garments, the chemicals released go into the municipal wastewater system and probably end up in the rivers and lakes around the cities or eventually into the sea. At each home, we wash only a few clothes. But when 8 billion people are washing their garments daily across the globe, it adds up to tons of chemicals, entering the water systems.

Mr Raaja Rajan lives close to the Cauvery river. Many fish and prawn species, which used to exist earlier are no longer available.

The end of the supply chain is the landfill where all the clothes end after their use is over. Synthetic, chemically dyed garments are built to last for a very long time. So, when we discard the garments, they take a long time to compost.

The usage of natural dyes was the practice for thousands of years in India and across the globe till the advent of synthetic colours about 160 years back. We didn't have the issue of pollution then.

If we use natural dyes, we can stop a lot of the pollution. In the case of natural dyes, we are not using any chemicals that will damage the environment. When clothes are washed, even if colour leaches into the wash water, and ends up in the rivers, lakes, or sea, there will be no impact, because it is not harmful. Also, even if we throw away the garment, the materials used are such that they will completely compost in reasonable time.

Thus, in the case of natural dyes, we don’t have a residual impact across the whole supply chain. In the production phase, during usage, and in the end, where we throw it away, we have a clean setup, with no residue.

Benefits of natural dyes

Environment: As already discussed, natural dyes are far better for the environment compared to synthetic dyes.

Safety. Today, due to the use of synthetic dyes, the water is highly contaminated. There are studies to show that all these chemicals have an impact on the endocrine system, and on the fertility system of both men and women. The safety of people who are working in the synthetic dye industry is at stake. The chemicals that come out as vapours go into their system. As a result, if they work for many years, they have health problems: respiratory issues, skin issues, other endocrine-based issues.

There are safety issues even for the people who wear the garments. The skin is the largest organ in the body. If there is leaching of chemicals from the garment, they will enter the system through the skin. These chemicals live in the system forever.

Water: Water is one of our most important resources especially in states like Tamil Nadu. Tirupur uses about 10 crore litres of water in a day for the dyeing industry alone. If we switch to natural dyes, we can reuse the water. As we are hardly polluting it, we can clean up the water very efficiently and quickly. Water used for dyeing can also be given to local farmers, for irrigation, or to grow dye-yielding plants.

Support to farmers and tribal communities: Natural dyes are grown on the farm or collected from tribal communities. They are not produced in a factory. Consider indigo. There are many benefits for farmers.

Nitrogen fixation happens when we grow indigo. So, it is good for crop rotation. Similarly, Marigold is good for inter crop.

People don’t have enough water to cultivate all the lands. There are some lands that are arid. Farmers don’t cultivate these lands because they don't have enough water. But there are some natural dye-yielding trees that don't require much water. So, if we provide support for the initial one or two years, then with the subsequent rainfall, the trees will grow, and provide, dye-yielding seeds.

Medicinal properties: Most natural dyes have good medicinal properties. They are highly antimicrobial and good for the skin. Even after wearing clothes for a week, we won’t have body odour. If we are wearing socks, we won't have a smell of the feet. For anybody suffering from eczema or skin-related issues, natural dye is an ideal product to use.

Possibilities with natural dyes

In the case of the Melange yarns, the sweater is made with natural colour. The cotton is dyed, and the yarn is spun and made into garments and various products. This process is highly scalable. So, if a customer wants say 1 lakh t-shirts or 1 lakh sweaters of a particular type, we can make it. This was a difficult process, 4 or 5 years back, when the process was largely manual. Today, large volume production is, is viable. It is also possible to ensure consistency of colour across the whole production.

Most of the production happens through garment dyeing, because the look and feel are more attractive to the customer. It gives a nice solid colour, with a very earthy finish. Here too, a reasonably large volume production is possible. We can do 20,000- 30,000 pieces in one colour. It is completely mechanized. (Indigo is the only colour which is done manually. All other processes are mechanized.)

In woven fabric dyeing, the fabric is dyed in a jigger. This is again a completely mechanized process where we can dye 500-meter lots. And here again, we can do 10,000 or 20,000 meters, because it is completely mechanized. Also, we can manage colour production and dyeing capacities completely in-house.

In hand yarn dying, some processes are still manual. Mr Raaja Rajan is in the process of mechanizing this system. He has had reasonable success, but we cannot dye hundreds of kilos in a day. However, we can certainly dye 50 kilos in a day. To scale up, it requires some effort in terms of probably a new machine development. Most of the other processes have used existing machines with maybe some minor alteration.

Screen printing with natural dyes is necessary to give character to the garment. Sensing the customer need, Mr Raaja Rajan has developed this methodology and has been awarded a grant for this project which has been successfully completed. Mr Raaja Rajan is already delivering orders, with about 9- 10 stable colours which can go in for printing. Previously, printing with natural dyes has been done through the traditional methods, like block printing, Ajirak, Kalamkari. While these methods produce beautiful products, they are not scalable. Screen printing can operate at scale with a few thousand pieces a day easily.

Challenges with natural dyes

Limited colour options. There are about 10- 12, colours that come directly from nature. Even with combination colours which are a little tricky to use, the colour options are limited.

Performance

Most people tend to compare natural dyes with synthetic colours. So, they want clothes made using natural dyes to last for a long time. Natural dye garments will not last as long as synthetic dye garments. In fact, they are meant to be so. In case of natural dyes, we want the colour to degrade and compost itself. But a small performance increase will be helpful.

Costs

Customers want clothes made using natural dyes to cost as much as a regular synthetically dyed garment.

Being a new industry, the raw material and production costs are higher. But as the volumes increase, costs will come down. If the raw material sourcing can happen through proper contract farming and other such measures, costs could come down further.

Government support

Natural dyes have been grouped with synthetic colours as textile dyeing and put in the red category. So, the regulations are highly restrictive for the industry. It is expensive to comply with the rules and norms of the current system. The government needs to recognize that natural dyes are not polluting at all. Efforts are on to educate the government but it is a long process.

Market potential for natural dyes.

General shift to a healthier living

Not only in the developed world, but even in developing countries like India, many people are shifting to a more conscious living system: organic food, electric vehicles, solar roof. They want to live a healthy life. They want to know what they are consuming, how it was made and where it was made. Such people will probably be the initial set of customers who will embrace natural dyes: people who want to know how the product was made and understand the benefits of natural dyes.

New rules and regulations

With some new rules and regulations that are coming in in Europe, the shift may happen much faster. Some regulations require brands to produce and deliver 100% compostable garments. Once that happens, natural dye is probably the only solution.

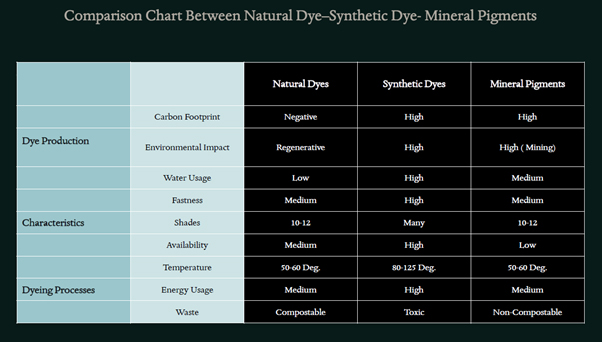

Comparison of natural dyes, synthetic dyes, mineral pigments.

Carbon footprint: The carbon footprint in case of natural dyes is negative. All the raw materials come from trees and shrubs. We don't need energy for the making of the natural dye. In fact, big trees like Myribalin, grow up to about 70, 80 feet. They sequester a lot of carbon, and we just use their seed. Synthetic dyes are produced with very high, energy-intensive, industrial, complex, methodology. In case of mineral dyes, we have to dig the ground.

Environmental impact: In the case of natural dyes, the waste can become compost. So, we can compost the waste and recycle it into the agricultural fields. Environmental impact is high in synthetic dyes and mineral dyes.

Water usage: Natural dyes use much less water than the other two processes, and the water can be reused.

Fastness performance: Natural dyes and minerals offer a medium level of performance. Synthetic dyes offer high performance levels.

Shades: In the case of natural dyes, there are only 10 to 12 shades. With synthetics, we can have as many colours as we want.

Availability: For now, the availability is medium, because the sources of natural dyes are highly concentrated in tropical countries like India. India can become a centre for natural dyes for the whole world. We have a variety of trees and plants.

Temperature: Natural dyes are on an average, made in a low temperature system. Synthetic dyes involve a very high temperature system. Minerals also need higher temperature. The processing time is also much shorter than synthetic colours.

Waste: In case of natural dyes, the waste is compostable. Synthetic dyes are toxic and mineral dyes are non-compostable.

Climate change.

If natural dyes take over 10-20% of global textile dyeing, all the colours must come from trees and shrubs which will have to be grown by farmers across the globe. So, there will be a general increase in tree cover leading to a negative carbon footprint.

Natural dyes will result in more healthy water systems, obviously. Today, as the rivers and the ocean are dying, they contribute a lot to the CO2 system in the atmosphere.

Natural dyes are more socially conscious and inclusive, because all are part of it. Farmers benefit in various ways. People who are working in the industry will not face health challenges. And it's a completely circular process. There is no residue anywhere in the whole process. So there’s no impact across the whole supply chain. Thus, the society benefits.

Q&A

Mr Raaja Rajan comes from a community of textile producers/weavers. They have been around for more than 300 years in a textile cluster called Kumarapalayam.

About 15 years back, his father complained that the water coming into the house had become coloured. The groundwater system was completely contaminated with the colours varying according to the dyes being used.

There were no effluent treatment plants those days. The wastewater from the dyeing units would be dumped into the Cauvery. The government introduced some stop gap measures but there was no long-lasting solution.

From a young age, Mr Raaja Rajan had been a nature lover. He started to probe deeper into what was causing the problem and how it could be solved. That is how he got the idea of natural dyes which had been used by earlier generations. Mr Raaja Rajan knew from history that India had been once a big centre for natural dyes. In fact, traders from across the world would visit India for its spices and textiles made with natural dyes. Mr Raaja Rajan felt natural dye was the ideal solution to the problem.

We are indulging in over consumption. We should consume less. And when we do consume, we must examine what it is made up of. Consider a simple cotton T shirt. Many people (maybe over 100) would have worked on it in various phases: farming, ginning, spinning, weaving, tailoring, dyeing, packing. lot of labour and love have gone into it. We should also understand how it was made, what raw materials were consumed, what process was used, what will happen after the usage is over, etc. We should not just look at the price. We should appreciate the human effort that has gone into the product.

Initially, everything was manual. So, the scale was limited. But anything done on a small scale will not make much of an impact on the environment. Mr Raaja Rajan’s target is to convert at least 20-30% of synthetic dyes being used today to natural dyes. In Tirupur, just one cluster processes 100 tons of fabric. Mr Raaja Rajan is only making about 500-600 kg of natural dye. So, there’s a need to scale up.

We should always ask how people will benefit. If we take care of the people in any industry, the environmental impact will be automatically reduced. Recently an adjacent factory had a labour shortage. Mr Raaja Rajan agreed to send surplus labour from his own factory. But the workers did not want to go there because that factory was using harsh chemicals. The health of workers is important. If workers fall ill, the entire family gets affected. The economic structure collapses.

People must feel the problem if it has to be solved. Today the messaging to the end consumers is not happening effectively. Few customers relate a T shirt to climate change or water supply. We must do a lot more to educate the consumers on what buying process they should adapt. They should be encouraged to look at how it was made, the environmental impact, etc. Most customers focus only on the price and design of the garment.

Colours are mostly synthetic. They are based on hydrocarbon molecules from petrochemicals. They tend to be water soluble.

Pigments are naturally produced and not water soluble. Their molecules are larger in size. Pigments do not enter the fibre. Their surface structure is such that they are metamorphic. The colours look different from different angles.

TDS increase during the process can be calculated. But the concept is somewhat technical. So, current campaigns are not based on TDS.

In case of synthetic dyes, at the end of the dyeing process, the TDS goes up to 18,000-19,000 units. In case of natural dyes, it only goes up t0 only about 1000.

Instruments are available to measure TDS in front of the consumer. So, the TDS figures can be included in the label.

The government, however, has been educated on TDS. In fact, multiple meetings have been held with government officials on the benefits of natural dyes. But the government machinery moves slowly.

It is possible that running campaigns with the involvement of college students and design institutes like NIFT can help. Students from these institutes are already doing internships. They get to understand the natural colour palette and how to come up with innovative designs. Their creativity and out of the box thinking can probably help in running impactful campaigns.

Hand tags are being used today. However, they can be deceptive and misleading. Clothes made with organic cotton, but using synthetic dyes are labelled as organic. Few brands with natural dyes are selling on Amazon as the commissions are prohibitive. One idea being used is attaching to the garment, a small hand tag and piece of fabric. If a drop of lemon juice is put on the fabric, it will bleach if it is a natural dye. This is a reliable test for natural dyes with the exception of natural indigo. Certifications are confusing for consumers. Most of them are an eye wash. Attempts are also being made to persuade the government to create natural dye marks.

Blue is a traditional colour, in fact the colour of our Gods. Indigo is grown on a large scale in India. It is very good for the soil and requires no irrigation or fertilizers or pesticides. It grows in about 3-4 months. The main cultivation areas are in Tamil Nadu with small amounts coming from Bihar/Jharkhand (once the largest growers).

Natural dyes are about 2.5 times more expensive than synthetic dyes. The dye component is about 30% of the garment cost. Mr Raaja Rajan’s brands are priced at about Rs 999 (round necked T shirts) which is not significantly higher than organic cotton T shirts which are priced at Rs 600-700.

Various attempts are being made to cut costs: melange, striped T shirts, yarn dyeing and larger volumes to cut raw material costs. Current effluent treatment costs Rs 40 per kilo. This will come down to Rs 5 per kilo if the government gives the natural dye industry some concessions.

People are today buying more than what they need. They should consume less. This way, for the same outlay, they can buy fewer but superior quality garments which are environment friendly. Of course, that calls for a change in consumer behaviour.

Based on his experience (dealing with H&M, Aditya Birla, etc), Mr Raaja Rajan feels that large brands are unlikely to take natural dyes mainstream. They have been pushing sustainability on a different plank- using the organic label. They have been selling organic as the best possible product available. If these large brands sell garments made using natural dyes, customers will start asking awkward questions.

In general, the large companies are driven by profits and costs. They have no concern for the environment, their people or vendors even though they may make several claims in this regard. They will do whatever reduces their costs.

Everyone is part of the value chain. We must respect everyone. That is why Mr Raaja Rajan has decided to develop his own brand.

Mr Raaja Rajan feels that innovations are more likely to come from smaller companies, not from larger existing players. Of course, these large players may play catch up later, once a concept is well established.

There is not much difference. But dyeing continuous knitted fabric is a challenge. New machines are needed. Discussions have begun with an engineering firm in this regard.

Educational institutions should define clearly what sustainability is. There are misconceptions and wrong interpretations. In this regard, we should take the advice coming from the developed countries with a pinch of salt. For example, all the synthetic dyes are made in Europe but not a single dyeing unit is operating there.